Schooling under bullets. Educational story from the Lyptsi municipality

How the teachers from Kharkiv region continued to teach according to Ukrainian curricula under occupation and taught children the most important lesson in their lives

Text by: Dmytro Syniak

Education is more than just knowledge. When the russian invasion hit Sloboda Ukraine, Ukrainian border towns and villages found themselves in almost the worst situation in all respects. Russian troops marched through the territory of the Lyptsi municipality day and night: Buryats, Chechens, Dagestanis, Tatars. The stores closed, the lighting disappeared (it is still not there). Complete darkness on the streets with new streetlights installed thanks to the decentralization reform has become one of the signs of putin’s onslaught. However, elementary school teacher Olha Istotska continued to work even under such conditions, and this became part of her resistance.

The material was prepared within the framework of the campaign “Municipalities and Educators at War” with the support of the Swiss-Ukrainian project “Decentralization for the Development of Democratic Education” DECIDE.

<= Olha Istotska was born in Sloviansk, Donetsk region. She lived in Lyptsi for 17 years, seven of which she worked as an elementary school teacher.

“Look, they don’t have russia on the globe!”

“You are making a heroine out of me for nothing – I didn’t do anything special,” Ms Olha is embarrassed. “I am sure that there were many people like me. Almost every teacher in our municipality was trying to do everything possible to protect the children and save the schools...”

The russians captured the Lyptsi municipality too quickly, and almost none of its residents had time to leave. The route to russia was unacceptable for most locals, and the territories controlled by the Ukrainian government were cut off by the front line.

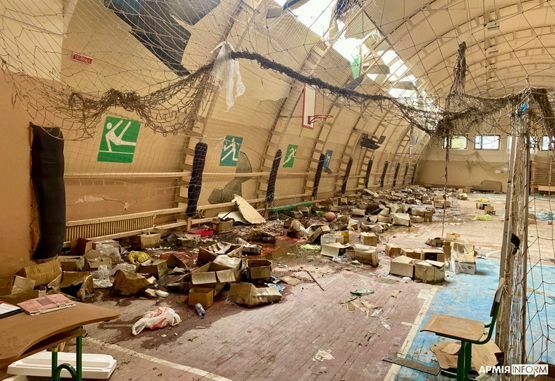

Russian troops behaved in the villages of the Lyptsi municipality in the same way as everywhere else: they robbed, abused, tortured. On all the new signs, the occupiers indicated that “the village of Lyptsi belongs to the Belgorod region”. Since there were few free houses, because the locals did not have time to flee, the soldiers arranged their barracks in schools, which were also fiercely looted.

The gym of the Lyptsi Lyceum after the stay of the russians =>

In the very first days of the occupation, Olha Istotska approached the russian commander of the units stationed at the Lyptsi Lyceum and said that she needed to take her own belongings from the classroom. He was surprised that the woman came alone: it turned out, she was already wanted.

“Why is there a Ukrainian flag on the wall in your classroom?!” the russian asked sternly.

“And what other flag should be there?” Ms Olha was surprised. “This is the flag of my country. Don’t russian schools have russian flags?”

“Yes, but your flag is obviously from ATO [Anti-Terrorist Operation]! This is visible to the naked eye!”

“Not from the ATO, but from Antarctica, from Vernadsky Research Base,” objected Istotska. “You look carefully: it has Antarctic stamps and signatures of polar explorers. It is indicated several times: ‘Antarctica’.”

The orc commander frowned, but did not argue further. He allocated two armed soldiers to Ms Olha. Accompanied by them, she entered her classroom.

“I took all the most valuable things: patches of members of the Antarctic expedition, gifts from Canadian and German schoolchildren with whom we corresponded, a letter to our class from the maid of honour of the Queen of England Elizabeth II, a book of artistic works of our students and even a penguin egg brought to us by the polar explorers,” says Ms Olha. “I could not take only two things. The first was actually that Antarctic flag from Vernadsky Research Base. The orcs flatly refused to give it up, saying that if I insisted I ‘could be in trouble’. One of the russian soldiers suddenly forbade me to take it. Apparently, he set his eyes on it. Later, the projector disappeared. When I left, I told the russians to water the flowers, ventilate the classroom and keep it clean. They nodded obediently. (A few days after that, when I passed by the school, a soldier said that ‘the flowers in the classroom were watered’). Although, to be honest, it seemed to me at the time that they never studied at school. I heard one of them, pointing to the physical globe, say to the other, ‘Look, they don’t even have russia on the globe!’.”

The unbreakable

Later, Ms Olha, having recovered a little from the shock, began to look for her students to begin the educational process.

One of the drawings of Lyptsi Lyceum students

“Probably, I needed these lessons more than the children,” recalls Ms Olha. “I had to do something so as not to go crazy. No, not even like that, I had to resist the occupation! For me, teaching was an element of struggle. I wanted to show that we, the local residents, did not give up, did not bow our heads in humility. We want to return to our former life and we want to prove to the russians that they did not succeed. Of course, I realized what I was risking, and I was scared. But I could not do otherwise.”

Fortunately, in the first months of the war, the invaders did not care about the local residents. They did not plan to open schools and did not expect that Lyptsi teachers would be able to organize the educational process not only without the Internet, but also without electricity. But they were wrong.

“Teaching children at home, I understood what real distance learning is,” smiles Olha Istotska. “Not the kind of training we had during the coronavirus pandemic, but training without printers, projectors, laptops – only with notebooks and textbooks. Of the gadgets, we used only cell phones, which the children used to take photos of lesson notes adapted for them. These phones could occasionally be charged at those villagers who had diesel generators. At first, I visited my students (the second graders) with my husband and gave them assignments. But it was problematic and dangerous. Then, I invited all the children who could safely reach my house to come to me.”

This news spread throughout the village, and children rushed to Ms Olha’s house. They were very interested – when else would they be able to get to their teacher’s house! Usually, 5–10 children gathered, completing tasks in mathematics and the Ukrainian language for several hours. Ms Olha considered these subjects to be the main ones. She knew what could happen when the orcs found out about her attention to the Ukrainian language, but she continued to teach anyway.

This is what Olha Istotska’s home school looked like

“One very important person for me told me at the very beginning of my teaching career, ‘A real teacher is the one who will stand up and teach in the midst of bullets’,” says Olha Istotska. “I remembered these words for the rest of my life, but I would never have thought that they would come true quite literally in my life.”

To monitor the situation, Ms Olha always opened the window wide during the lessons, and when explosions began to ring nearby, she ordered the children to quickly dress and run to the neighbour’s basement – there was no basement in her own house. For the little ones, it was an exciting adventure, which they were extremely happy about, and only Ms Olia realized what each shelling could turn into for all of them. At that time, the number of people killed by shelling in the municipality reached dozens.

When the shelling intensified, people began to flee from the occupied territory little by little. Then, Ms Olha announced that she would teach all willing elementary school students – from any school. She did not want to leave her native place for anything. In order to confirm her decision, Olha Istotska decided to defend the title of teacher-methodologist. It was scheduled for March, but then postponed indefinitely due to hostilities.

“I don’t think anyone has received the title of teacher-methodologist like this before,” Istotska laughs. “In June, it was possible to call from us only from the neighbour’s garden – there, by some miracle, mobile communication still worked. But one could not even dream about Internet connection. Then, I called my colleague and asked her to record my report on a voice recorder and then send it to the Kharkiv Academy of Continuing Education. I hang the sheets with the text on the fence and read my report aloud. And I still managed to defend my title.”

Latvia

However, in July, Olha Istotska had to admit that it was time to leave the municipality.

“At first, we were really waiting for our boys,” the woman recalls. “There were even days in May when all the residents of Lyptsi were convinced that the Ukrainian army would be with us in a few days. But, unfortunately, that did not happen. Instead, the russians became much more evil. They began to search the homes of local residents. Two searches were conducted in our house, and once they even took my husband ‘for inspection’. Another time, these creatures disrupted our lesson. Then, they said they had to take our car. I had to interrupt the lesson that had just started and go out to them with my husband to try to convince them. We needed that car. As a result, we listened to a two-hour speech about how they hate all other Slavs: Ukrainians, Belarusians, Poles, but Ukrainians, of course, the most. They frankly said that they would have gladly killed us, but they were afraid of their own, russian justice. My husband was threatened with being forcibly sent to clear up the mines on the roads. When they did take the car away, I told my husband that I didn’t want to go through this anymore. Besides, who knows if next time the russians will be able to cope with the desire to kill us.”

After several attempts, Olha Istotska and her two children finally managed to leave the municipality – in the back of a truck. Her husband was not released. (Later, he witnessed the liberation of the village by the Ukrainian army). Only one way remained open from Lyptsi – to russia. But Ms Olha did everything she could to cross the border with the European Union as soon as possible. She did not even visit her russian relatives. And in a few days, she was already in Latvia.

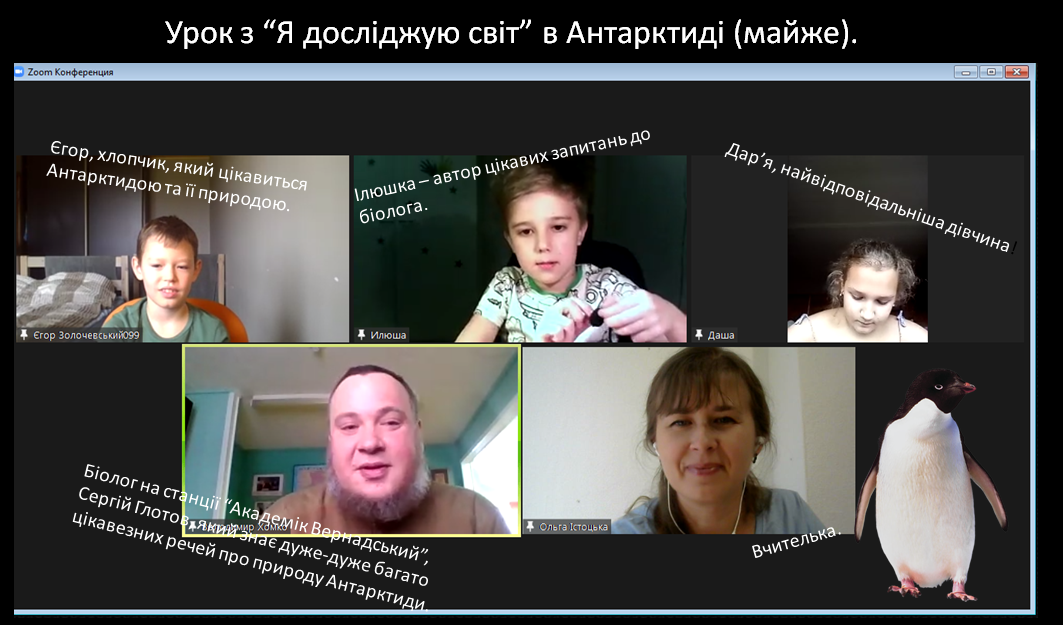

The first thing Ms Olha did when she got temporary housing was to write to her students and their parents. After some time, she gathered a good half of the class and announced the start of distance learning in the “coronavirus” format. But in reality, this learning turned out to be much more interesting. Ukrainian soldiers, Antarctic polar explorers already familiar to the children, and German friends of Ms Olha joined the online lessons. Several times, “to make learning more fun”, she held her lessons in the evening, in the “pajama party” format. Despite the peculiarities of the online format, she managed to conduct physical education lessons outdoors. Now the teacher is working on the preparation of the performance – with costumes, spectators and guests, and this is also in an online format.

Biologist of Vernadsky Research Base Serhii Hlotov at Ms Olha’s online lesson

“Now, it is much more difficult to work than during the coronavirus pandemic,” Olha Vasylivna admits. “By definition, the coronavirus ‘distance learning’ had an end: we all knew that sooner or later we would return to the school desks, that there would be a vaccine, and so on. And now, nothing is known about our future. When will we be back? What will happen to the premises of our lyceum and, in general, to our municipality? What will happen to our Ukraine? But we believe in victory and we really want it to come as soon as possible.”

Monitor screen during one of Olha Istotska’s online lessons, in which volunteer from Kharkiv Mykhailo Ozerov took part

Anti-tank obstacles of bureaucracy

When I ask whether Ms Olha wants to return to Ukraine, she answers that she literally dreams of it. But she does not understand how to live in her native land: she received her last salary for February. On the other hand, a Ukrainian teacher is in great demand in Latvia, because there, “many people are convinced that soon, Ukrainian will be needed by everyone”. So now she teaches a group of adult Latvians for free, and earns a living with online Ukrainian lessons for Ukrainian children scattered across different countries.

“I know that I will return home,” says Ms Olha. “I will endure everything and – I will return. But, probably, it is still too early to go now...”

Olha Istotska’s lesson for adult residents of Latvia includes studying recipes of Ukrainian cuisine. Studying the topic “vegetables” while cooking borscht together

“Decentralization” addressed the head of the education department of Lyptsi municipality, Yaroslav Kostovych, with a request to comment on the situation with the payment of salaries to teachers. It turns out that anti-tank obstacles of the Ukrainian bureaucracy are preventing the receipt of payments.

“The problem of our municipality is that its education department is not a manager of funds,” said Mr Yaroslav. “This was done from the very beginning, and it greatly hindered our work: I had to contact the village council for each payment. I spoke about it more than once at the sessions and meetings of the executive committee, but everything remained as it was. Therefore, our education department does not have its own money. For example, we have now received 65 brand new laptops from UNESCO. But in order to give them to those teachers who are not in the municipality, for example, Olha Istotska in Latvia, funds will also probably be needed. We will think about how to solve this problem...”

The head of Lyptsi village council, Oleksii Slabchenko, said that the funds for paying salaries to municipality teachers have been in the accounts of the village council for a long time. But they could not transfer them to the teachers, because the russians destroyed all the documents and stole all the computers. There is no staff list, nor even a list of those to whom salaries are owed. All this had to be restored from scratch, and this restoration could only begin from the middle of the first month of autumn: russian troops left Lyptsi only on 11 September. Also, there are almost no employees left in the village council: Oleksii Slabchenko had to rely only on himself and the accountant, who miraculously did not leave during the occupation. But when the necessary documents were finally restored, a military administration was established in Lyptsi by decree of the President of Ukraine from 1 October of this year.

“If this decree had stated that the newly created military administration could dispose of the budget of Lyptsi village council, there would be no problems,” says Oleksii Slabchenko. “But since this was not indicated, now the military administration does not have the right to pay salaries to teachers according to the documents prepared for the village council. Everything must be redone.”

However, Oleksii Slabchenko still has hope for the Verkhovna Rada, which should recognize the legal succession of all military administrations of the Kharkiv region. The Ukrainian Parliament has already done this for the municipalities of the Kherson region. But it is not known when to expect its resolution.

The shot up schools

“Before the occupation, we had 10 secondary education institutions, of which only four lyceums are currently working online,” says the Lyptsi village head. “640 students study in these lyceums, although before the war, there were 1,100. We managed to keep most of the teachers, but quite a lot of

school premises were damaged. One school in Lyptsi, one in Vesele, and one in Ternova suffered considerable destruction, and a fire broke out in the school in Hlyboke village; part of the school premises burned down. Now, a special commission of the village council and the Kharkiv regional administration is conducting inspections of all schools, drawing up reports on the damage caused. And in the spring, I hope, gradual reconstruction will begin.”

Russian “gifts” left in the Lyptsi municipality

However, it is now very difficult to predict how many families and, accordingly, children will return to their native places. It is quite possible that the municipality will no longer need as many schools as there used to be. For example, in Lyptsi, the centre of the municipality, 860 of the 3.5 thousand residents remained; in Vesele village – 136 out of 1,360 inhabitants; in Peremoha village, where 650 people once lived, two remained; and Ternova village, which had more than 600 inhabitants before the war, was completely depopulated. Despite this, Oleksii Slabchenko is optimistic.

“Now, we really have very few people, but most of those who left want to return,” he says. “I get the question ‘Can I go home already?’ almost every day. I am trying to explain to everyone that there is no need to rush at the moment. Gas is still far from everywhere, there was (and there is) no electricity, and the Internet works from a single Starlink, in which you have to change the batteries all the time. The russians stole eight school buses and all the cars belonging to the village council. So it would be better for those residents who left to wait for spring. However, when it gets warmer, people will no longer be able to hold back. They will definitely return to their native lands, because they have always done so, wherever life throws them. There is something special about our places, it is very difficult to leave them forever...”

Pre-war photos from the archive of Olha Istotska

Tags:

war stories education war report

Область:

Харківська областьГромади:

Липецька територіальна громадаSource:

Decentralization Initiative Press Centre

02 February 2026

Смарт-спеціалізації та ланцюги доданої...

У Києві відбулася презентація ключових результатів масштабного дослідження «Смарт спеціалізації регіонального...

02 February 2026

Decentralisation: Highlights for January

Decentralisation: Highlights for January

At the beginning of each month, the Decentralisation portal summarises the Government’s and Parliament’s decisions...

02 February 2026

«Європейський код доступу»: Як налаштувати українську систему інвестування на фінанси ЄС

«Європейський код доступу»: Як налаштувати...

Представники ГО «Інститут громадянського суспільства» представили проєкт, який має на меті змінити систему державного...

30 January 2026

Fifteen communities in the region unite around...

Leaders of 15 communities in Ivano-Frankivsk region signed a memorandum of cooperation in the city of Halych,...