Redrawing the map: Denmark mixes hard and soft criteria

Ulrik Kjaer is Professor of Political Science at the Department of Political Science and Public Management at the University of Southern Denmark. His main research interests are local democracy, mayoral leadership, local elections, and local parties. He has published in international journals such as European Journal of Political Research, Local Government Studies and Urban Affairs Review.

Ulrik Kjaer is Professor of Political Science at the Department of Political Science and Public Management at the University of Southern Denmark. His main research interests are local democracy, mayoral leadership, local elections, and local parties. He has published in international journals such as European Journal of Political Research, Local Government Studies and Urban Affairs Review.

Executive Summary

In Denmark, major structural reform began on January 1, 2007. The existing 275 municipalities were amalgamated into 98 in a fairly speedy process. Less than three years after a commission published a white paper with recommendations on the principles for amalgamating municipalities, the municipal map of Denmark was redrawn and the new municipalities were up and running.

The decision to reform was made by the central government, which decided that the new municipalities had to have at least 20,000 inhabitants. However, it was left up to the municipalities themselves to determine which neighboring municipalities to team up with in order to meet this minimum size. Supplementing the hard criterion of size, the municipalities were also guided by a soft criterion, cohesion: preferably, the new municipalities were to fit with already existing patterns of local identities, commuting or consumption. If neighboring municipalities were already cooperating and had strong bonds, they were expected to amalgamate with each other. Also, one loophole was allowed: smaller municipalities located on islands could be exempted from meeting the size requirement.

Meanwhile, the input of an arbitrator was offered, with a highly respected former mayor and minister travelling to some of the harder cases and facilitating discussions as to how to draw the new map. The map of Danish municipalities was finally redrawn. Even though not everybody was equally satisfied with the new borders, criticism has been minimal, as center-periphery tensions within each of the new amalgamated municipalities was anticipated from the start. However, even though new political cleavages have formed along geographical lines, there have also been patterns that might mitigate potential conflicts, such as the mobilization and election of a good number of councilors from the periphery during the first local elections in the newly-formed communities. Successfully implementing the amalgamation was a very complex balancing act, and the window of opportunity for amalgamations will probably not open again anytime soon in Denmark.

The Danish case

Denmark is a Scandinavian country with 5.7 million inhabitants. Political decentralisation is quite strong and local governments account for half of all public expenditures. On January 1, 2007, major structural reform was launched to reduce the number of municipalities from 275 to 98, and the number of provinces from 14 to 5.

The municipal map of Denmark had been stable since the previous amalgamation, in 1970, when more than 1,100 municipalities were merged into 275, but at the beginning of the new millennium discussions resumed about redrawing the map once more. The number of municipalities was reduced from 275 to 271 back in 2003 when the five municipalities on the remote island of Bornholm merged. This amalgamation was voluntary and based on a local referendum held in 2001, where 74% of the population voted in favor of establishing the municipality of Bornholm.

This voluntary amalgamation was one of the factors stimulating a broader debate that started in the summer of 2002. This led to the establishment of a committee to investigate the structure of the public sector in Denmark. Based on the committee’s white paper published in January 2004, a political deal was made in Parliament in summer 2004 and the reform process was finally launched at the beginning of 2007. Reducing the number of municipalities from 271 to 98 of course means that the average size of Danish municipalities has significantly increased, going from 20,000 to 55,000.

Table 1. Local government structure in Denmark pre and post 2007 reform.

|

|

Pre-reform

2006

|

Post-reform

2007

|

|

Number of municipalities

|

271

|

98

|

|

Number of provinces

|

14

|

5

|

|

Average number of inhabitants per municipality

|

20,027

|

55,582

|

|

Percentage of municipalities with < 10,000 inhabitants

|

47.6%

|

4.1%

|

|

Percentage of municipalities with > 30,000 inhabitants

|

14.8%

|

74.5%

|

Source: Calculated based on official records from Statistics Denmark

The size of municipalities is very often the feature of amalgamation reforms that attracts the most attention. This is warranted, since the size of a municipality is important in relation to its functions and not the least how it can take over more public sector tasks as a result of amalgamation. In the Danish case, municipalities supplemented their responsibilities for daycare centers, public schools, elder care, water and sewage systems, local roads, and social service with, for instance, specialised social care and unemployment services. The population size of the municipalities also determines if and how the supposed fruits of merging can be reaped, such as economies of scale.

Between the decision to increase the size of the municipalities and potential positive impacts, there are, however, several important steps, first among them being the decision as to who should amalgamate with whom. And deciding who should amalgamate with whom is far from trivial. A new map will not materialize just by choosing the size of the new municipalities, as specific borders must be drawn between the new municipalities. For many citizens, this is important. For some, the assessment of the new municipality will probably depend on which neighboring municipalities are selected for merging. In this paper on the Danish case, the focus will be on how this necessary and important, yet often somehow overlooked, process of amalgamating municipalities was undertaken.

The approach

Although Denmark was among the European countries that began to talk about altering its municipal structure nearly two decades ago and its amalgamation is now fully implemented, the definitive history of this structural reform has yet to be written. Many aspects of the reform have, so far, not been systematically evaluated and the final verdict cannot be made as to whether the reform was successful in economic, democratic and professional terms. However, a number of studies have been conducted focusing, for instance, on political trust,[1] internal efficacy,[2] satisfaction with local governments,[3] economic effectiveness,[4] local party systems,[5] and so on. In this paper, the focus is on how the new borders between the current larger municipalities were drawn, as this question has not been systematically investigated. The few studies touching upon the geographical dimension of the new map are mentioned but apart from these, the paper builds on the legal rules, political agreements and historical accounts of the process. Hard facts have been supplemented with author’s assessments based on observations concluded in the research process.

Criteria for redrawing the map and its pace

January 9, 2004 marked an epochal date in Danish municipal history. On this day, the commissioned white paper on the future structure of Denmark’s public sector was published. Then-Minister of the Interior Lars Løkke Rasmussen later proclaimed that reform would be initiated and that municipalities were going to be amalgamated. Nothing was formally decided until June 24, when an agreement was reached between the government and its parliamentary coalition, but the signal was clear and unmistakably already in January: smaller municipalities would soon cease to exist.

However, even though it was now clear that municipal amalgamations were in the horizon, this brought up a new question: Who should amalgamate with whom? For the process of changing an existing municipal structure into a new one raises at least three questions: 1) How long should the process of redrawing the map take? 2) Who should make the decision who joins with whom: municipalities voluntarily or the central government by fiat? 3) Which criteria should amalgamations be based upon?

In terms of pace, the process of redrawing the map was quite fast. Once political agreement was reached in June, the municipalities were given until the end of December to negotiate with their neighbors and report to the Ministry on how they planned to proceed, meaning who they wanted to amalgamate with. Based on these preferences, a first draft of the new map was produced by the beginning of March 2005 and after further negotiations, described below, the map was finalized in June 2005. Given that the question of who merges with whom is far from trivial—some would argue that for the municipalities themselves it is almost existential—the process was clearly quite fast.

The government was operating under a deadline, as local elections, according the electoral law, were scheduled for November 15, 2005. By having the new municipalities ready for this date, the elections would be held for councils in the new municipalities. This meant that in 2006, the newly-elected councils took over the functions of planning committees for the new municipalities with full responsibility for all municipal tasks. The new structures became effective as of January 1, 2007, while the old councils continued for all of 2006 as sort-of “caretaker governments” before stepping down January 1, 2007. This transitional arrangement appears to have been unproblematic.

In terms of choice, the process of having the municipalities themselves negotiate with their neighbors and make an official request as to who would merge with whom proved to be a fairly open and voluntary process. Indeed, municipal councils were occupied with these considerations and negotiations in the fall of 2004, trying to find out whom they should “marry.” Should a smaller rural municipality merge with the city located to its west or to its east? Or should it invite other neighboring rural municipalities to merge with together to avoid being a part of a large urban center?

In fact, the amalgamations were not totally voluntarily. First of all, choosing who to amalgamate with was the second part of the process, as the first part—whether there should be an amalgamation at all—had already been decided at the central level. Secondly, there were certain constraints in the choices available in the form of criteria laid out by the government and constraints from neighboring municipalities. The bottom-up process of finding a suitable partner or partners was a series of interconnected games, a kind of puzzle to be solved since some neighboring municipalities might have different plans—as in, “sometimes you like your neighbor more than your neighbor likes you.”

In terms of the formal criteria amalgamating municipalities were to meet, these were quite straightforward. The new municipalities had to be made up of neighboring municipalities and have a total of at least 20,000 inhabitants. To be accepted for this criterion, an existing municipality could enter a binding partnership with a neighboring municipality of more than 30,000 inhabitants, although municipalities consisting of an island did not have to meet the size requirement for a partner-municipality. This was the main hard criterion, but other recommendations were also given to municipalities. While the formal minimum size was set at 20,000 inhabitants, the government recommended that municipalities aim at 30,000 inhabitants.

A “soft” criterion was added when the Minister recommended that municipalities aim for cohesion, meaning the new municipalities should be formed by communities that were already linked through common patterns such as trade and commuting. In other words, the newly amalgamated municipalities should not start from scratch but already have bonds and some sense of “belonging” together. This criterion was soft since it was supposed to guide the municipalities into establishing relatively coherent amalgamated municipalities, although there were no specific indicators as to what “cohesion” more specifically meant.

Formally, it was up to the national parliament to pass a law establishing the new municipal map and who was to merge with whom, which happened on June 29, 2005. In short, this process can be described as initially a top-down process where the central government decided that municipalities were going to amalgamate. This was followed by a bottom-up process where the municipalities themselves negotiated with neighbors. In another top-down process, the final decision was made centrally, including the resolution of cases where local processes could not come up with a new arrangement.

Solving the difficult cases

In most cases, the Danish puzzle was relatively easy to solve: several smaller rural municipalities merged with the larger, more urban municipality in their area. In terms of inhabitants, the new municipalities met the hard criterion: often the population size actually exceeded the minimum of 20,000 and even the recommended 30,000, simply because this was inevitable when a number of smaller municipalities who could not together reach 20,000 merged with a larger municipality that already met this size requirement.

As for cohesion, in many cases this was also met. The neighboring urban center was already the place, where kids attend secondary school, people took part in the cultural life, went shopping, and so o n. However, there were also difficult cases, where drawing the new map was far from a self-evident “no-brainer” and where different solutions were possible. These difficult cases can be grouped by three distinct characteristics:

-

The islands. Apart from the peninsula of Jutland, Denmark consists of more than 400 islands, just over 70 of them inhabited. Before the reform, five of these islands were municipalities of their own—in two cases more than one municipality—but with less than 20,000 inhabitants. These islands are surrounded by the sea and they have a very strong local identity, making it difficult to claim that merging with a municipality on mainland Denmark would form a cohesive municipality. To solve this problem, a loophole was included in the legislation: if a municipality formed a partnership-agreement with a larger neighboring municipality, the smaller municipality could be exempted from the size requirement. All of the five islands with less than 20,000 inhabitants chose this option, so that today, five islands have their own municipality despite their small size while some of their tasks, not least in regard to social policy, are taken care of by the larger municipality that they were already connected to by a ferry. Also, two mainland municipalities used the model, resulting in a total of seven out of the current 98 municipalities not meeting the 20,000 inhabitants-criterion.

-

The “in-between” municipalities. These municipalities could go looking for mergeable neighbors in different directions, since they were situated in-between two major urban centers. A new municipality to the north could make as much sense in terms of cohesion as a new municipality to the south, which gave them a choice. But even there, problems could arise. For instance, the southern part of the small municipality amalgamating to the north might have felt less connected to the northern neighbor than to the southern one. In order to “fix” these cases, municipalities could be split: even if such an option was not explicitly promoted, at least there was no criterion that only entire municipalities could merge. Thus, in some cases a local referendum was held in parts of smaller municipalities over whether to follow the main part or join another amalgamation. In 19 municipalities, this led to a minor adjustment of the borders. In some cases, the municipalities themselves asked the residents in smaller parts for their opinion, but in 12 cases a local referendum took place upon the recommendation of an arbitrator.

The government had asked a highly respected individual, Thorkild Simonsen, to act as a mediator. A former Interior Minister from a different party than the then-Government, Simonsen was also the former mayor in one of the bigger Danish cities, but was no longer in office. He travelled to the municipalities where there had been a lot of debate and discussed with locals whether there was broad popular support for the suggestion to amalgamate reported from the council to the government. In some cases, these talks resulted in the council calling a local referendum.

-

The “trouble-makers:” These were municipalities who would not or could not find anybody to merge or cooperate with, and did not meet the size criterion. Three municipalities did not fit into the puzzle after the voluntary part of the process. One of the municipalities did not want to participate in amalgamation since they had the lowest municipal tax rate in Denmark and a merger with neighboring municipalities would inevitably result in higher taxes. The central government had to then include this municipality in an amalgamation already formed by its neighbors. The two other municipalities were neighbors, but one of them refused to merge with the other, because the second municipality had just gone through a major scandal with the mayor overspending, making risky investments with municipal funds, and leaving his municipality with a huge debt. The central government forced these two municipalities to merge after agreeing to subsidize the new municipality and allowing them to continue with two different tax rates for an interim period.

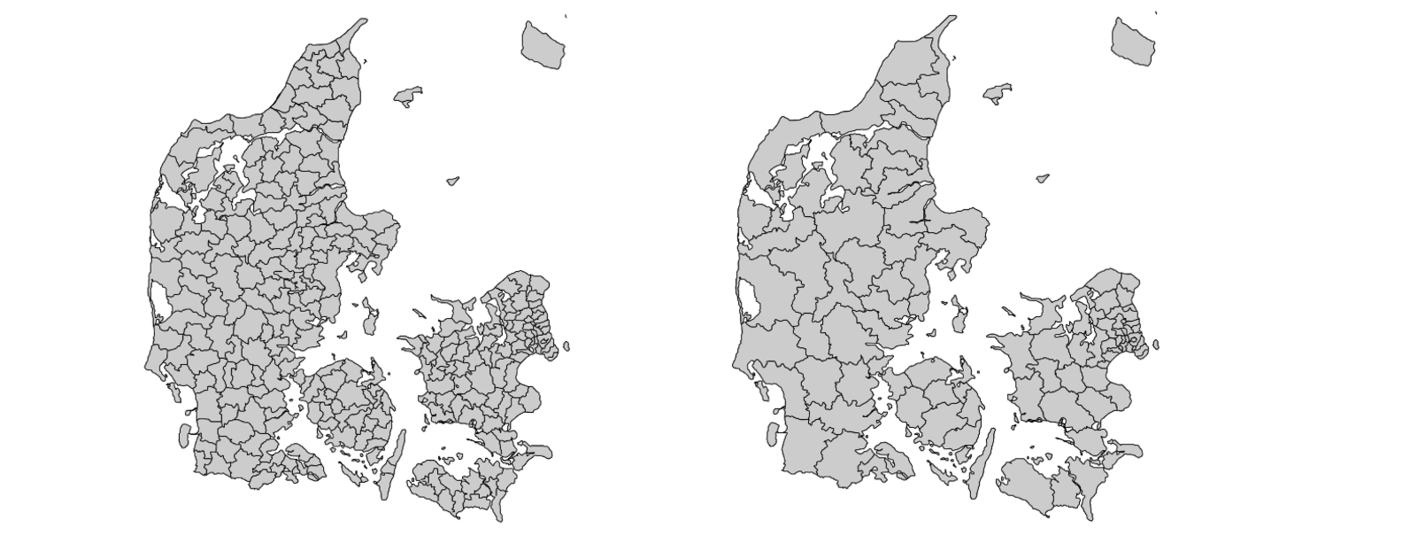

Once these difficult cases were solved, the amalgamation was finalized and the new map of Denmark could be presented with 98 municipalities instead of 271, as shown on the map. In fact, 239 municipalities were amalgamated into 66 new municipalities while 32 of the original municipalities continued in their original form: the seven small municipalities that were exempted, and 25 larger municipalities that remained unchanged, including Denmark’s three largest cities.

Figure 1. Map of Denmark and its municipalities before and after amalgamation

In all, less than three years after a commission presented its white paper with some ideas and suggestions, Denmark’s new municipalities were up and running. A lot of political decisions had been made, including which functions the municipalities should have in the new structure and how the new borders should be drawn. Some local politicians were likely happier about the outcome than others, but in general the new map was accepted as a reasonable solution. Most Danes were prepared to accept and live with the result.

The final assessment is that, even though it was a huge and difficult task to merge municipalities and satisfy everybody with the new map, the task was carried out quickly and successfully with not too much dissatisfaction. In retrospect, a few minor blemishes can be pointed out. Firstly, the area around the capital Copenhagen in the easternmost part of the country was almost unaffected by the reform. The municipality of Copenhagen itself did not merge with anyone and many of the surrounding municipalities in the metropolitan area did not merge, whether with the capital or with each other, as many of them have populations just a little over 20,000. The municipal structure in the area of Copenhagen has been debated for many years, so it was odd that almost nothing changed in this area, while the rest of the country was engaged in a major redrawing of municipal borders. This also means, in terms of spatial configuration, that municipalities in the western part of the country are now larger than in the eastern.

Secondly, there were a few municipalities that could not agree on a name for the new municipality and five of them ended up with a hyphenated name. So when the five municipalities of Ringkøbing, Egvad, Videbæk, Skjern, and Holmsland merged into one municipality that named itself Ringkøbing-Skjern, the hyphen seems signal that they did not entirely meet the cohesion criterion in the same way as many other municipalities where the name of the largest city or a distinct name for the area was chosen. Two of the five municipalities changed their names soon after amalgamation and got rid of the hyphen, but Ringkøbing-Skjern and two others are still hyphenated, with division not only at play in local politics but even built into the name of the municipality.

Potential intra-municipal, center–periphery tensions

The phenomenon of hyphenated municipalities points to a more general concern regarding the amalgamation of municipalities, namely whether merging several municipalities into one might unleash political tensions between the center of the new municipality, that is, the more urban municipality, and what is now the periphery of the new municipality—the smaller municipalities on its outskirts. The smaller municipalities were used to having their own center with a town where the town hall, the local school, and so on, were located, but now there might be fears that municipal activities and institutions will also be merged and located in the more urban part of the new municipality.

A recent study has demonstrated that the sense among residents of belonging to the municipality has not, on average, been affected by amalgamation, but also that this differs between those living in the center municipality and those on the periphery. Living in the periphery apparently makes Danes feel less attached to the new municipality than does living in its center.[6] This suggests at least a potential for conflicts along this political cleavage: maybe the old borders survive in the heads of the councilors and residents, even after they have been removed from the official map. In general, even though there has been debate in some municipalities over how activities and investments have been distributed among the old municipalities now amalgamated into one, so far, this has not evolved into dog fights.

Three potential explanations can be put forward as to why the center-periphery tensions have remained somewhat under control:

-

The soft criterion of cohesion: This has encouraged the establishment of municipalities where bonds between the different parts of the new municipality already existed. Even though the old municipality is now a part of a municipality with a diferent name, it might be more acceptable if this is the city where residents were already commuting to work, where they did some of their shopping and where “their” football team is based.

-

The first local elections: In the newly amalgamated municipalities, voters in the periphery were more mobilized to cast a preferential vote[7] for one of their local candidates. This meant that the smaller parts of the amalgamated municipalities ended up with more candidates elected to local councils than their share of the population would have suggested. Indeed, in around half the amalgamated municipalities, councilors living in the periphery actually outnumbered councilors living in the bigger city.[8]

-

The question of City Hall: While in some amalgamated municipalities, a new City Hall was built in the center to host the amalgamated municipal administration, in many municipalities the opposite strategy, “keeping the lights on,” was followed.[9] This was a concept according to which the municipal administration was reorganized, but at the same each and every one of the old city halls was still used, with case handlers and civil servants still working out of the buildings.

It’s hard to say exactly how dramatic the political fights over how to design the new amalgamated municipalities have been. Or how disappointed some Danes might have been to see public activities and investments moving away from their town and into the city in the center of the new municipality. But the tensions resulting from the new center-periphery cleavage seem not to have been overwhelming, and the establishment of relatively coherent municipalities, reorganizing without moving all activity to the center at once, and making room for the periphery to mobilize in local elections seem to have smoothed transformation from one municipal structure to another.

Amalgamation fatigue

With a new municipal structure established, one final question could be: is a long-term solution? There’s no way of knowing for sure, but an important indication materialized on December 3, 2015. On this day, a local referendum was held in the two neighboring municipalities of Holstebro and Struer in which residents were asked if the two municipalities should amalgamate. And the answer was a clear NO, with 54.8% and 67.9% rejecting another amalgamation. Both municipalities underwent amalgamation in 2007, so it looks like one of the decisive factors behind rejecting a new round of amalgamation reflects a kind of “amalgamation fatigue.” Merging municipalities is not an easy task: it means a lot of extra work and it can raise anxiety over what the consequences of the amalgamations will be.

When amalgamations are bundled in a major reform with a government supported timeline for the process, there is an open window of opportunity to discuss and pursue amalgamation. It would be harder for municipalities today to undertake the amalgamation process on their own. In addition, it would be hard to find a neighboring municipality that was not already in the 2007 process and is likely to suffer from ”amalgamation fatigue”.

Conclusions

The structural reforms implemented in Denmark in 2007 led to a major change in the structure of local government. It has probably also resulted in some Danes thinking they are better off, while others think they are worse off, in the end. The reform and its various elements have received both good and bad reviews.

The overall assessment of Danish reform by this author is that it was a difficult exercise that actually turned out to be less troublesome than might have been expected. It is, of course, difficult to measure the exact consequences of amalgamation, such as whether it resulted in economic gains through economies of scale, since it overlapped with a global financial crisis that has made it difficult to distill the effects of the reform.

So, what might have been the reasons behind this relatively successful reform and what are the lessons for other amalgamators, outside Denmark?

-

The fundamental reason behind the reform was quite simple and formulated as “professional sustainability” or “professionalization of scale.” With more and more complex cases for the municipality to take care of, the smaller municipalities were having difficulties maintaining a professional setting where the necessary specialization and professional development could be nurtured, and recruiting highly qualified professionals was beginning to be a challenge. Amalgamating served as a solution to the municipalities: if you grow, you can maintain your functions. Having a clear motivation for the reform is an advantage.

-

The process was relatively short: as soon as the central government decided that “this is going to happen,” the timeline was relatively tight. This moved the difficult decisions forward.

-

The mix of involuntary and voluntary processes helped: the central government decided which municipalities should amalgamate but not with whom. That was a local decision.

-

Difficult cases were resolved, in some cases by having a loophole for cultural or historically important island municipalities, and in others by involving a respected mediator.

-

The soft criterion of coherence signaled that locally reasonable solutions should be sought.

Since the amalgamations were concurrent, central government agencies and the association of local governments were also better prepared to help with all kinds of question about how to amalgamate municipalities.

Denmark’s 2007 Structural Reform was a handful—and some are happier about the process and results than others. However, the Danish local government system is strong and viable today—maybe due to the reform, and maybe not. Yet, without a relatively smooth process regarding redrawing the map, Danish municipalities would probably have been worse off today.

Further readings

Ministry of the Interior and Health (2005). The Local Government Reform in Brief. Copenhagen: Ministry of the Interior and Health (https://english.sim.dk/media/11123/the-local-government-reform-in-brief.pdf).

Copy editor: Lidia Alexandra Wolanskyj

All terms in this article are meant to be used neutrally for men and women

Prof. Ulrik Kjaer has participated at the International Expert Exchange, "Empowering Municipalities. Building resilient and sustainable local self-government", organized by U-LEAD with Europe Programme in December 2019. His speech delivered during one of the workshops is to a great extent depicted in this article. Despite its late publication, the article is still of significant relevance for the current discussion on decentralization reforms’ next steps in Ukraine.

In the name of the U-LEAD with Europe Programme, we would like to express our great appreciation and thanks for both inputs of Prof. Kjaer. The article will be included in future online publication Compendium of Articles.

Compendium of Articles is a collection of papers prepared by policymakers, Ukrainian and international experts, and academia after International Expert Exchange 2019 and 2020, organized by U-LEAD with Europe Programme. The articles raise questions in the fields of decentralization reform and regional and local development, relevant for both the Ukrainian and the international audience. The Compendium will be published online in Ukrainian and English languages on the U-LEAD online recourses. Please, follow us on Facebook to stay informed about the project.

If you have any comments or questions about the Compendium of articles or this article in particular, please contact Yaryna Stepanyuk yaryna.stepanyuk@giz.de.

This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union and its member states Germany, Poland, Sweden, Denmark, Estonia and Slovenia. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of its authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the U-LEAD with Europe Programme, the government of Ukraine, the European Union and its member states Germany, Poland, Sweden, Denmark, Estonia and Slovenia.

[1] Hansen, S.W. (2013). Polity Size and Local Political Trust: A Quasi-experiment Using Municipal Mergers in Denmark. Scandinavian Political Studies, 36 (1), pp 43-66.

[2] Lassen, D.D., & Serritzlew, S. (2011). Jurisdiction Size and Local Democracy: Evidence on Internal Political Efficacy from Large-scale Municipal Reform. American Political Science Review, 105 (2), pp 238-258.

[3] Hansen, S.W. (2015). The Democratic Costs of Size: How Increasing Size Affects Citizen Satisfaction with Local Government. Political Studies, 63 (2), pp 373-389.

[4] Blom-Hansen, J., Houlberg, K., Serritzlew, S., & Treisman, D. (2016). Jurisdiction Size and Local Government Policy Expenditure: Assessing the Effect of Municipal Amalgamation. American Political Science Review, 110 (4), pp 812-831.

[5] Kjaer, U., & Elklit, J. (2010). Party politicisation of local councils: Cultural or institutional explanations for trends in Denmark, 1966-2005. European Journal of Political Research, 49 (3), pp 337-358.

[6] Hansen, S.W., & Kjaer, U. (2020). Local territorial attachment in times of jurisdictional consolidation. Political Geography, p 83.

[7] In Denmark, preferential votes are important for the selection of candidates.

[8] Jakobsen, M., & Kjaer, U. (2016). Political Representation and Geographical Bias in Amalgamated Local Governments. Local Government Studies, 42 (2), pp 208-227.

[9] Bhatti, Y., Olsen, A.L., & Pedersen, L.H. (2010). Keeping the lights on - Citizen service centres in municipal amalgamations. Administration in Social Work, 35 (1), pp 3-19.

20 February 2026

Місцева статистика: Як перетворити розрізнені...

У Києві відбулася стратегічна зустріч "Статистика громад", організована Державною службою статистики України за...

20 February 2026

I_CAN launched a nationwide rollout of its Public Investment Management Training Programme for local governments and...

20 February 2026

Language of Development Part 2: Funds and Instruments of EU Cohesion Policy

Language of Development Part 2: Funds and...

With the “language of development”, we describe not only the goals and principles of EU regional policy, but also...

19 February 2026

Анонс: вебінар «Обговорення змін до Порядку...

Які практичні кроки мають здійснити керівники та педагоги, щоб ефективно впровадити ключові зміни до Порядку...