How Estonia’s reforms empowered local government

Rivo Noorkõiv is the CEO at the Geomedia Consulting and Training Centre

Rivo Noorkõiv is the CEO at the Geomedia Consulting and Training Centre

Rivo Noorkõiv has been contributing to the implementation of Estonian administrative reform in recent years. Noorkoiv was a member the administrative reform board of experts for the Estonian Government as well as regional reform commissions. His specializations include strategic planning in both public and private sectors, regional development and change management.

Executive Summary

The article is a comprehensive analysis of the administrative reform process in Estonia. The author describes a situation in the country before the reform (from an economic, administrative, territorial point of view), explains the evolution of the processes preceding the start of the reform, and brings the reader to the point of country's history when the need to increase and harmonise the capacities of Estonia’s municipalities become obvious to the most of stakeholders. Administrative reform, which started in 2016, was divided into four stages, and the author describes all of them as well as the achieved results. At the end of the article, nine general learning points identified based on Estonia’s experience of administrative reform are named. The paper would be especially valuable to all interested in the international experience of conducting complex reforms, organisation of administrative territories and local governance.

Background

Administrative Reform had been circulating in Estonian society for decades when it finally took off in June 2016. That was when the Riigikogu or Parliament passed the Administrative Reform Act.[1] This had been preceded by a long list of reform plans and attempts, and can be seen as the result of nearly 20 years of evolutionary development.

The population of Estonia was 1.329 million as of 2020. With a territory covering 45,227 km², Estonia’s population density 30.5 inhabitants per km.² The territory of Estonia is divided into 15 maakond or counties, which are administrative units without separately elected representative bodies or any other significant independent powers.

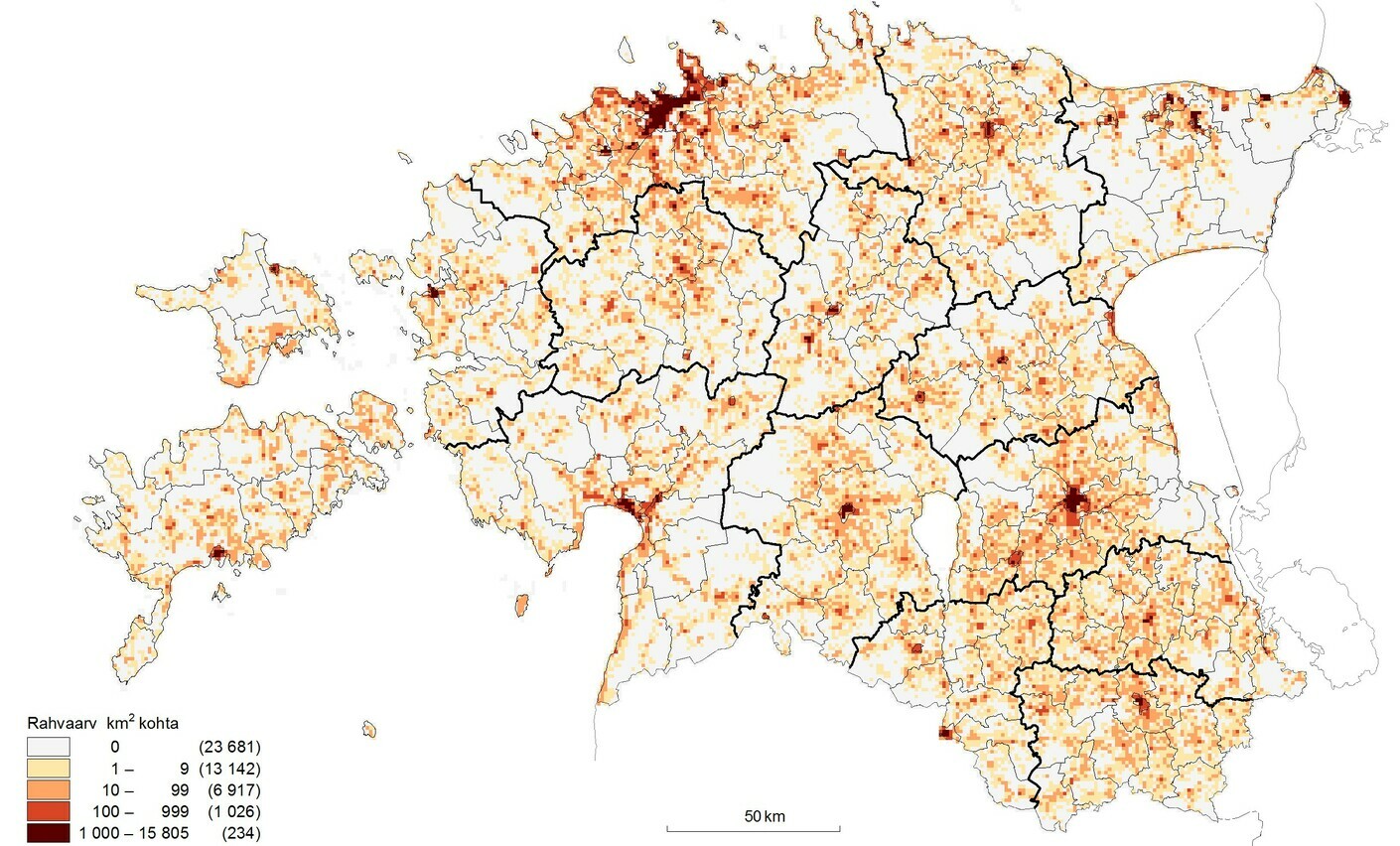

Figure 1. Population density 2016 (Source: Statistics Estonia)

Source: Statistics Estonia

Compared to the rest of the European Union and OECD[2] countries, regional differences within Estonia are high, with 32% of the population living in the capital, Tallinn (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Population distribution in municipalities, as of Jan. 1, 2017

Source: Statistics Estonia

With economic activity and attractive jobs concentrated in larger urban areas, regional disparities in economic growth have been deepening. Together, a declining and greying population, and concentration in urban areas have weakened the development prospects of municipalities in rural areas. The movement of jobs into cities, the globalization of the business environment, growing mobility in daily work and leisure, and longer commute routes have led to a need to deal with the challenges of local development, including the development of new kinds of capacities.

The tradition of Estonian local government in its present form dates back to the 19th century and the Rural Municipality Act of 1866, and continued in the independent Republic of Estonia until 1940. Conceptual work on establishing the basic principles of modern local government started in the late 1980s. Since 1993, a one-tier local government system has operated in Estonia since the reorganization of the legal foundations and revenue base of local government. By autumn 1993, when all the administrative units were granted their status, there were 256 towns and rural municipalities in Estonia, each with the autonomy to make decisions and organize issues of concern to the local community.

Regardless of size, local governments were expected to offer the same functions throughout Estonia and provide the same services to their residents. Since 2018, when county governments were terminated, local authorities in the centre of the county were assigned new functions for joint implementation: they were now responsible for the registration of divorce, marriage, name-related procedures, and even change of gender. According to current Estonian law, local authorities in each county are also expected to jointly plan the development of their county.

In order to decentralize powers, local governments have the power to form municipalities or city districts on their territory, with limited self-government functions. These formations are regulated by local government statutes. Local government territories are divided into population centres: cities, towns, small towns, and villages.

According to the Local Government Organisation Act,[3] local government has the right, the authority and the duty of a democratically elected body to independently organize and manage local issues according to law, based on the legitimate needs and interests of the residents, and with a view to the specific development of the local government. The activities of local government are organized and managed by a representative body elected by the residents: this elected council approves the executive body. Local governments may also delegate some of their duties to private or non-profit organizations. In addition, they may form organizations to provide services, act as shareholders in such organizations, and become members of foundations or non-profit organizations.

Estonia’s National Audit Office has consistently emphasized the need for administrative reform. Over the years, its audits have demonstrated that there is no hope for positive change in the capacities of local governments without such reforms.[4] [5] The Chancellors of Justice also pointed to the problem of Estonia’s local government system in terms of protecting fundamental civil rights. They had found that a large share of Estonia’s local governments were unable to ensure equal quality and access to public services.[6]

At the Pärnu Management Conference in 2011, it was declared that “the observation of the reality of local governments leads to an irrefutable conclusion: many of them are not real, but illusory. Objectively and subjectively, they are unable to perform their functions and provide high-quality public services to the people living in their territory. In short, administrative reform is indispensable.[7]” The Local Government Capacity Index[8] also showed that there was an obvious need to increase and harmonize the capacities of Estonia’s municipalities.[9]

Following the failure of yet another reform attempt, two studies were commissioned by the Ministry of the Interior in 2015, to assess the location and accessibility of private and public services,[10] and to map the competences and specializations of local government staff and their professional development needs.[11] Meanwhile, awareness of the ageing and declining populations of the majority of local authorities grew, along with the understanding that this was a long-term trend.[12] An older population and sparse density in a territory meant higher per capita service delivery costs. Clearly, the uniform provision of services cannot be resolved by local governments with a lower tax base without the subventions from the state. As each ministry wants to ensure the provision of its own services, more targeted allocations will inevitably be needed as the gaps among local governments grow. This, in turn, means reducing the autonomy of local governments, as the income base grows dependent on decisions made by the central government. But, given the resources available to the state, it is unlikely that the state will be able to provide significantly more funding to cities and rural municipalities in the near future without redistributing functions between the central government and the local governments.

In Estonia, the share of local governments in total public spending is close to 25%, compared to Denmark with 64%, in Sweden 47%, in Finland 41%, and in Norway 34%.[13] About a third of the local government revenues in Estonia comes as a central government grant. Moreover, Estonia has the lowest share of local tax revenues in Europe: 3.5%—compared to Sweden, with 55.1%, Finland 46.2% and Denmark 35.4%).[14] Also the Local Autonomy Index for Europe[15] and comparative national analyses[16] show that the shortcomings in autonomy of Estonia’s local government system mainly come from weak financial independence, and generally the limited contribution of local governments into policy design at the central or regional level.

An OECD report on the state of public governance in Estonia[17] showed that, given the number of tasks performed by municipalities, the small number of inhabitants in those communities is a problem. The typical concerns of the small local governments included: having few employees, but many tasks and, therefore, selective execution; fighting consequences rather than taking preventive action; and needing to provide financial support to residents instead of services. There were not enough specialists with the necessary qualifications, and workloads were too small workloads to allow for specialization.[18] At the same time, red tape has increased, resulting in more work on documents and less contact with residents.

Still, local government councils and executives in Estonia were considered well-structured and fairly powerful participants in civil society.[19] In larger local governments, the dominant power distribution was more pluralistic, while in smaller ones it was more elitist.[20] The lack of rotation of the elite might mean that people trusted their electors, were satisfied with their decisions, and do not want local political change. In larger local governments, coalitions among various political parties or electoral coalitions had to be formed in order to come to power. Thus, arguments that small local governments mean more democracy than larger ones or that local government mergers are a threat to local democracy and to voters’ ability and opportunities to control local government and the local elite turn out not to be true from these findings.

In conclusion, the lessons from failed reform attempts and a broad knowledge-based understanding of the need for change and possible solutions for the local government system in Estonia contributed to the implementation of administrative reform. It was also important that politicians demonstrated the willingness to agree on reform in 2016.

The goals of Estonia’s administrative reform

When the Government was formed after the 2015 election, undertaking administrative reform was included in the coalition agreement, although the question of specific merger criteria was left open. As the parties had not put down specific principles, there was an opportunity to shape suitable rules during discussions. The coalition agreement appointed the Prime Minister to be in charge of the reform, taking on the role of a negotiator to identify common interests and establish the position of Minister of Public Administration.

The Administrative Reform Act set out goals[21] that were rather general: the purpose was to support an increase in the capacity of local governments to offer high quality public services, using regional conditions for development, increasing competitiveness, and ensuring more consistent development.

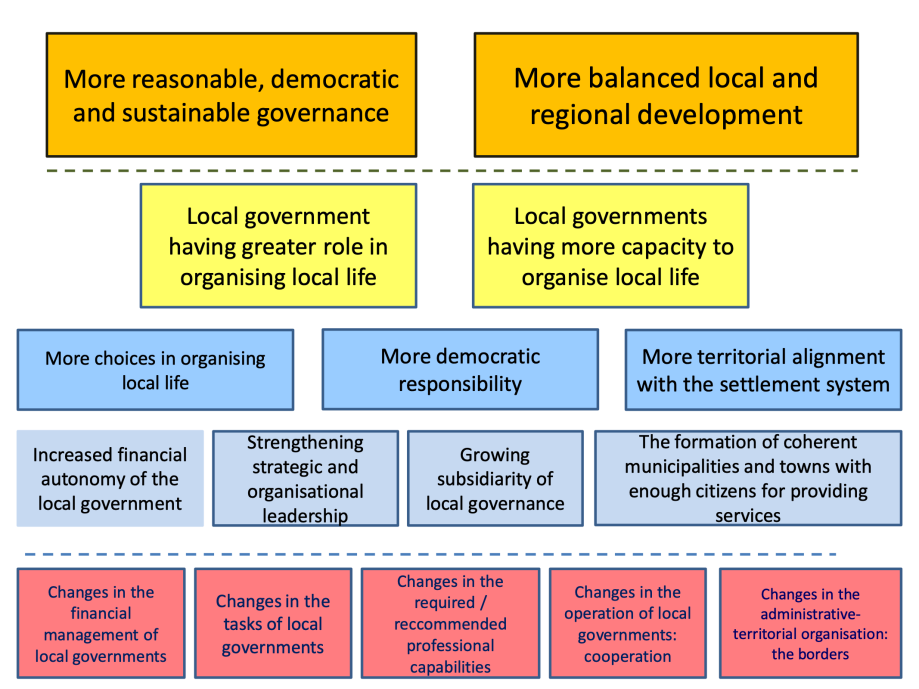

The expert committee set up to prepare for the reform drew up a “goal tree,” indicating the priorities the reform was to contribute the most to (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Goal tree for local government reform in Estonia

The goal tree established the importance of local governments assuming a greater role in organizing local life and improving their capacity to do so. The goals included greater choices in the organization of local life, greater democratic responsibility and more territorial alignment. This meant greater financial autonomy, stronger strategic and organizational leadership, increased subsidiarity, and sufficient population groups for services to be effectively provided. At the “root” of all this were five pillars: changing the functions of local governments, funding, ensuring professional capacity, establishing levels of cooperation, and, finally, organizing administrative territories. Changes to the borders of local governments were only one of the measures in the reform package for developing Estonia’s local government system.

The reform was designed to be implemented in several stages.[22] The first stage, a prerequisite to the next stages, was the re-organization of the local government layout by merging local communities. Next came the restructuring of regional administrations; third were changes in the functions of local governments. The fourth and final stage was changing in the funding of local administrations. Given goals that were all important at the same time, but which would be difficult to implement simultaneously, this approach has been sufficiently confirmed by comparative analyses of local government reforms,[23] and that knowledge was used in the design of Estonia’s reform.

Local government has two major roles in a democratic society: (a) self-organization to develop the community and democracy; (b) the provision of public services, supporting the economic activity of the municipality, and efficiency. The main question here was—and not only in Estonia but in all democratic societies—how to ensure that the two roles are organized effectively and sustainably, together with the necessary mechanisms and balance between the two.

Setting the criteria

The Administrative Reform Act introduced a minimum population size of 5,000 inhabitants per local administrative unit, and 11,000 as a recommended size. Exceptions were foreseen for cases where the territory of the new local government would be more than 900 km² and the combined population would be at least 3,500, and for island administrations. For other criteria, it was recognized that the law did not need to prescribe changing circumstances in detail, and the central government should not limit the autonomy of the local government to organize and manage local life. There is no ultimate ideal population size for local government, but the size should reflect the context of a specific time and place, based on evidence and political agreement.[24]

A similar approach, determining reform criteria only by population numbers, had been applied in other countries, such as Finland and Denmark. This meant that the content of the reform had to be determined by each local government itself: identifying logical merger options, negotiating various aspects of local life, and offering solutions to build up the new local government.

Merger contracts

The Administrative Reform Act required all merging local authorities to conclude merger contracts in which issues and solutions that were important to the merging sides were agreed on, including future investments. The law gave the merger contract a central role, laying the foundation for the new local administration to put together a development plan and budget strategy. Contracts were concluded for four years and could be amended with the support of a majority of at least two-thirds of the relevant council members.

Merger grants and social guarantees

The Estonian government had been promoting the merger of local governments since the 1990s, in order to achieve the formation of functional towns and rural municipalities with larger territories and populations. Based on the Administrative Reform Act, merger grants were paid to those local governments that opted for a voluntary merger in 2016. The rate of the grant for municipalities with the minimum population size was €100 per resident, instead of the more typical €50. The minimum merger grant sum was €300,000 and was capped at €800,000 for each merging municipality, as opposed to the standard €150,000 and €400,000. As a one-time bonus, municipalities that either had at least 11,000 residents or incorporated an entire county as a result of a merger would receive an additional €500,000.

The outgoing chairs of local councils, and rural and urban mayors were paid one-off compensation on the expiry of their terms. If the person had been in the position for less than one year before the announcement of the new local council election results, the compensation was six times the average monthly salary for that over the previous two years; if the length of service was one year or more, the compensation was 12 times the amount.

Stages of the reform

Administrative reform was divided into four stages. The first of these, and the prerequisite for subsequent stages, was re-organizing the borders of municipalities and cities via mergers. Then came the restructuring of regional administrations. Next came changes in the functions of local administrations and, finally, changes in their funding.

The boundaries of local governments were also changed in two stages: 1) voluntary mergers and, 2) the mergers initiated by the Government of Estonia. The voluntary stage of the reform lasted until January 1, 2017. By then, local government councils that were unable to meet the criteria had to submit a request for a merger decision to the county governor. A month later, the Government issued a regulation to approve the mergers based on local initiative. The second part of this stage, mergers initiated by the Government, lasted from January 1 to July 15, 2017. During that time, the government proposed mergers to local governments, and by May 15, they had to respond to the proposal.

In some cases, the community wanted to merge with a different local government. This happened with 26 villages. Several local governments ran surveys to find out which merger option their residents preferred, but several local councils rejected the wishes of the people and blocked the transfer.

All mergers entered into force after the next local council election. By June 15, 2017, all local governments had to hold elections in their communities. Where this did not happen, the county administrator took over responsibility. In mid-July, 90 days before the elections, the Government proposed changes to the administrative territorial structure. All the changes were implemented on the day that the results of the local council elections were announced in October 2017. The changes to the functions and organization of local administrations entered into force on January 1, 2018, when the new administrations started work.

During the first stage of the reform, local governments had considerable discretion in choosing their merger partners.[25] Each local government had to find the best way to organize local life, respecting its historical experience and the identity of the community. On one hand, decision-making and freedom were given to the local level to make more suitable choices from the viewpoint of their community. On the other, this led to some mergers with questionable interconnectedness, since they were not based on shared activity spaces, where the centres and hinterlands of influence would be linked. Previous merger experiences and personal relationships among community leaders also played a role in the formation of mergers.

At the stage of voluntary mergers, 160 local governments or about 80% out of 213 decided to merge voluntarily: 183 rural municipalities, 30 cities and 47 merger areas. Before the mergers, 23 local governments fulfilled the criteria and four islands applied for exemptions under law not to join with any other local government. By the beginning of 2017, 26 local communities did not meet the minimum population criterion of 5,000 inhabitants and did not request merger decisions. After the voluntary stage, there should have been 102 local governments in Estonia.

The process

The Minister of Public Administration, acting under the Ministry of Finance, was responsible for the administrative reform and its criteria. With the Minister’s directive, a Committee of Experts was set up to actually prepare the Administrative Reform. In order to provide guidance for the reform, three regional committees were also set up.

During the preparations, the Ministry of Finance drew up guidelines for local authorities, which contributed significantly to solving the issues on the ground and streamlining the process. Local authorities also had access to free consultations, assistance in managing the merger process and support for research. Local governments could engage merger consultants free of charge and received support in using the services of merger coordinators. Most local governments made use of this assistance provided by the state.

The Administrative Reform also led to some court actions when some local governments argued that the reform conflicted with the Constitution. The legality of the reform was debated twice in the Supreme Court. First, whether the Administrative Reform Act that established the general conditions for implementing the reform, including the authorization of the Government to decide on the forced mergers of local governments, was in accordance with Estonia’s Constitution. When the Supreme Court declared the Administrative Reform Act constitutional on December 20, 2016, it was clear that the reform would not be reversed.

Next, some local governments challenged the forced merger procedures in the Administrative Court and the Supreme Court. The Constitutional Review Chamber of the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional and invalid only the cap of €100,000 for covering the costs of Government-initiated mergers foreseen in the Administrative Reform Act. Since administrative-territorial re-organization was a national issue, the Constitution required that the costs be borne in full by the central government. On other issues, the Supreme Court dismissed the suits. The share of voluntary mergers could have been higher, as some of the local governments stopped merger preparations in the expectation that the Supreme Court would overturn the Administrative Reform Act. As a result, some municipalities did not have enough time after the Court decision to conclude negotiations by the deadline.

The Results

Since Estonia’s administrative reform, there are 79 municipalities: 15 towns and 64 rural municipalities.

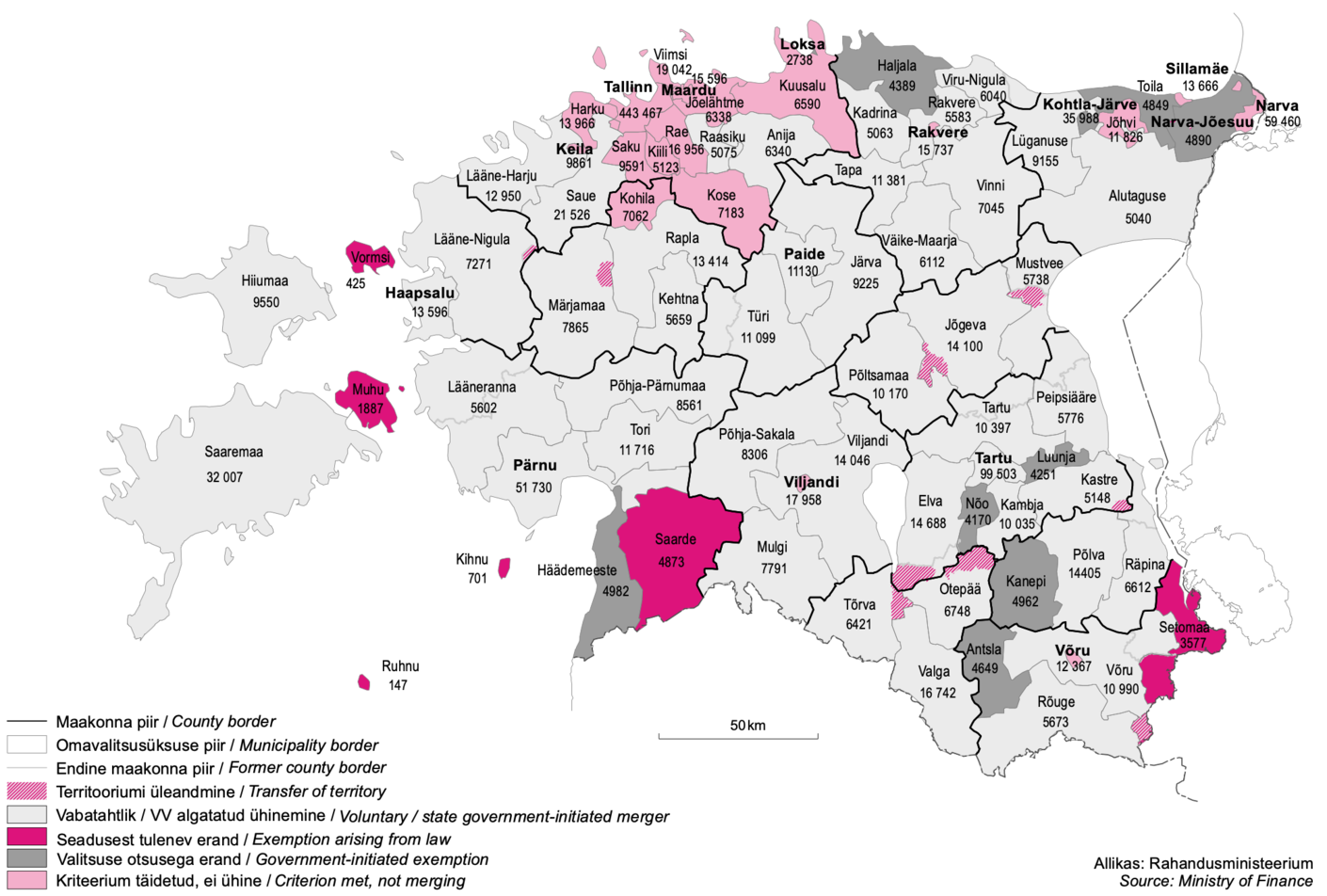

Figure 4. Local governments in Estonia after Administrative Reform

About two thirds of the current local administrative units or 51 new municipalities were formed, during this process. All told, 45% of Estonians live in these municipalities, covering 91% of the country’s territory. The population distribution after this process is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1: Changes in number of inhabitants and territory of local governments

|

Local governments |

in 2017 |

after the reform 1.01.2018 |

|

Total |

213 |

79 |

|

< 5,000 inhabitants |

169 |

17 |

|

5,001 – 11,000 inhabitants |

28 |

34 |

|

> 11,000 inhabitants |

16 |

28 |

|

Average population |

6,349 |

17,152 |

|

Median population |

1,887 |

7,739 |

|

Average territory (km²) |

204 |

550 |

|

Median territory (km²) |

180 |

512 |

Mergers led to new names for the local administrative units as well. In 51 voluntary mergers and 36 non-voluntary mergers—71% in all—the name of one of the merging towns among rural municipalities was retained as the name for the new entity. In four cases, the name was preserved and the categorial term was changed. In 11 cases or 22%, a new name was given to the new municipality.

One unintended consequence of Administrative Reform was the need to change village names, as there could not be villages with the same name within one municipality. A total of 50 village names were changed and 9 villages were combined. Two new villages were created when the settlements were transferred from one municipality to the another. Altogether, there were such transfers in seven counties during the reform in a total of eight municipalities, and the process involved 26 villages. There were many more cases of villages that were not able to complete the transfer due to opposition in the local council. As of 2020, several villages were continuing to request the transfer process. After administrative reform, rural municipal or city districts were formed in only about 10% of municipalities.[26] The formation and development of such districts and community councils is not widespread and this process has become more complicated than expected.

In the local council elections held in October 2017, 1,729 city and municipal council members were elected from among 11,804 candidates. The average age of those elected was 49.5, with 1,234 (71%) men and 495 (29%) women. Turnout for the election was 53%.

Meanwhile, Administrative Reform led to the loss of 335 jobs in local governments or 9%, going from 3,762 jobs to 3,426.[27] In terms of both the number and percentage, the largest decrease is understandably the positions of chief administrators and secretaries in local governments. The proportion of staff involved in the organisation and provision of services has gone up, while proportion of support staff went down. Local governments need to continually invest in the professional development of their staff, to make the public administration system more people-centred, flexible and efficient, to make better use of local development advantages, and to cope with socio-economic differences within the country.

Merger grants for local governments conducting voluntary mergers were worth €64.6 million. Of this amount, about €50 million covered local government investments agreed in merger contracts, €8.6 million went to severance payments, and €6 million covered other expenses.

The lessons learned

Lessons can be learned from the reforms in every country, but the homework needs to be done locally in order to identify suitable solutions for particular circumstances.

At least nine general learning points can be identified based on Estonia’s experience of administrative reform:

- Things will happen when there is political will and favourable public opinion.

- Communication is key. Make sure clear information is available and a proper communication plan is carried out. It is extremely important to communicate why the reform is taking place and what will be improved for residents as a result.

- Encourage co-creation by engaging broad expertise and knowledge, and involving different stakeholders.

- Base mergers on unambiguous criteria, including clear conditions to allow for exceptions. Then stick to the reform goals.

- Set up a clear, realistic reform timeline and communicate it widely. Ensure voluntary change management through incentives and recognition, with clear rules that reflect both best practices and negative experiences.

- Encourage local municipalities to make their own agreements about their future through merger contracts.

- Provide government support to local leaders and local governments. Offer assistance in the form of merger consultants and coordinators, as well as help providing all necessary information, process design, organizing info days, seminars, and research.

- Make it known and understood that the new local governments will be compensated should they have less state support compared to pre-reform levels.

- Be prepared to deal with the additional tasks the reform entails: registering name changes, territorial changes, changes in statistics and data registries, and so on.

Further trends

With its Administrative Reform, Estonia moved towards an administrative arrangement that is more common in northern Europe, where the size of municipalities is relatively larger and their functions include the provision of more extensive services than in southern Europe. Now that the administrative-territorial stage of the reform has taken place, changes in local governments and their administrative powers are at the heart of the next steps of the reform. This gives more place to solutions regarding the quality, accessibility and efficiency of public services, as well as the development of local democracy, and the balance of local and central government policies.

In reviewing the responsibilities of central and local governments, the principle of subsidiarity, of doing the things at the lowest administrative and political level possible, and as close as possible to the inhabitants, is key. Unless residents participate in decisions affecting them directly, local government loses its meaning.

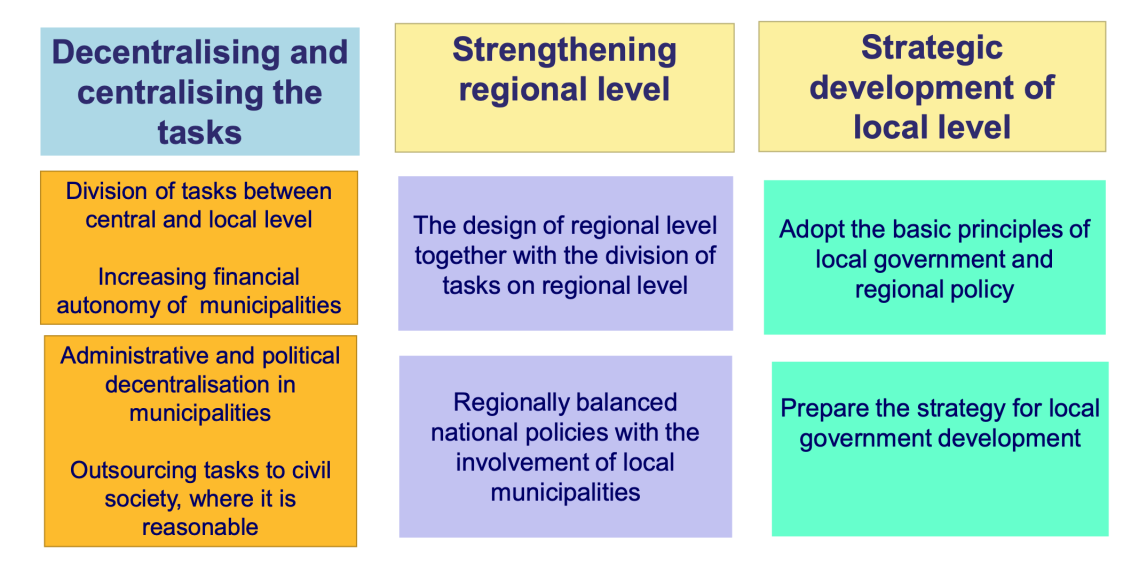

At the same time, the opposite of decentralisation is centralisation and it is important to put both of them into practice (see Figure 5).[28] The functions of local government can be carried out at different territorial levels, starting from community activities within the local government up to national-level cooperation. In all this, the main decision-making is about which tasks should be performed by local governments and which ones should be delegated to wider-scale regional level. It is also a question of choice, whether the county or township level is a suitable level of cooperation or a larger territorial unit is more appropriate.

Figure 5. Suggested follow-up to Administrative Reform

Local governments have the responsibility to use taxpayers’ money to achieve certain goals and to do so efficiently. One of the prerequisites for it is fiscal autonomy, including expanding the local revenue and tax bases. The current tax system in Estonia has become a barrier for municipalities. The local governments’ revenue generating opportunities and the allocation principles of the Equalization Fund need to be revised because, among others, national funding for completing certain tasks should take the actual location of specific needs more into account. More decision-making power should also be given to the local level in situations where the central government provides ad hoc aid to local governments. Resources should be channelled into the local governments’ revenue base and the Equalisation Fund. Incentives should also be offered to increase local governments’ motivation to develop their particular business environment.

National support is needed for innovative reorganization among local governments and for smart solutions to service provision, including pilot projects where necessary. Also, the IT capacity of administrations needs to be increased, as well as the use of IT solutions to develop local web portals, e-services and e-voting systems, and to bring auto-filled e-forms into use.

To conclude, administrative reforms are a unique phenomenon that is connected to historical administrative practice and the future vision of individual countries. Its implementation depends on the combination of consensus and political will at a specific moment.

Further Readings

Administrative Reform Act. https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/514072016004/consolide

Local Government Organisation Act. https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/509012014003/consolide

Administrative Reform 2017 in Estonia, Collection of Articles https://haldusreform.fin.ee/static/sites/3/2019/01/lg_reform_eng_finale_screen.pdf

Copy editor: Lidia Alexandra Wolanskyj

All terms in this article are meant to be used neutrally for men and women

Rivo Noorkõiv has participated at the International Expert Exchange, "Empowering Municipalities. Building resilient and sustainable local self-government", organized by U-LEAD with Europe Programme in December 2019. His speech delivered during one of the workshops is to a great extent depicted in this article. Despite its late publication, the article is still of significant relevance for the current discussion on decentralization reforms’ next steps in Ukraine.

In the name of the U-LEAD with Europe Programme, we would like to express our great appreciation and thanks for both inputs of Mr. Noorkõiv. The article will be included in future online publication Compendium of Articles.

Compendium of Articles is a collection of papers prepared by policymakers, Ukrainian and international experts, and academia after International Expert Exchange 2019 and 2020, organized by U-LEAD with Europe Programme. The articles raise questions in the fields of decentralization reform and regional and local development, relevant for both the Ukrainian and the international audience. The Compendium will be published online in Ukrainian and English languages on the U-LEAD online recourses. Please, follow us on Facebook to stay informed about the project.

If you have any comments or questions about the Compendium of articles or this article in particular, please contact Yaryna Stepanyuk yaryna.stepanyuk@giz.de.

This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union and its member states Germany, Poland, Sweden, Denmark, Estonia and Slovenia. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of its authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the U-LEAD with Europe Programme, the government of Ukraine, the European Union and its member states Germany, Poland, Sweden, Denmark, Estonia and Slovenia.

[2] Eurostat Regional Yearbook, 2018, Regions at a Glance, OECD 2018 (https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/oecdregions-and-cities-at-a-glance-2018_reg_cit_glance-2018-en#page1)

[3] Local Government Organisation Act https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/509012014003/consolide

[4]Riigikontrolli tähelepanekud haldusreformi läbiviimise riskide kohta. (ENG: The National Audit Office's observations on the risks of implementing administrative reform) https://haldusreform.fin.ee/static/sites/3/2017/09/kovid_haldusreformi_riskid_riigikontroll.pdf

[5] Riigikontroll (2012), Avalike teenuste pakkumise eeldused väikestes ja keskustest eemalasuvates omavalitsustes. (ENG: National Audit Office (2012) Preconditions for the provision of public services in small and remote municipalities)

[6] Õiguskantsler (2009), Postimees 2.03.2009 (ENG: Chancellor of Justice (2009), Postimees 2.03.2009) http://www.postimees.ee/88980/oiguskantsler-haldusreformi-labiviimine-naitab-riigivoimu-tugevust

[7] Jüri Raidla Pärnu Juhtimiskonverentsil 2011. (ENG: Jüri Raidla Pärnu at the Management Conference) http://www.delfi.ee/news/paevauudised/arvamus/juri-raidla-eestiriigi-pidamist-on-vaja-radikaalselt-muuta.d?id=59748604

[8] Sepp, V., Noorkõiv, R., Loodla, K. (2009), Estonian Local Government Capacity Index: Methods and results, 2005-2008. Cities and rural municipalities in figures, pp 10-42, Statistics Estonia. https://vana.stat.ee/publication-download-pdf?publication_id=18268

[9] Noorkõiv, R., Ristmäe, K. (2017), Kohaliku omavalitsuse võimekuse indeks 2013, Artiklite kogumik, Eesti kohalik omavalitsus ja liidud - taastamine ning areng 1989-2017, Lk. 310-341. (ENG: Noorkõiv, R., Ristmäe, K. (2017), Local Government Capacity Index 2013, Collection of Articles, Estonian Local Government and Associations - Restoration and Development 1989-2017, Lk. 310-341.

[10] Tartu Ülikool RAKE (2015), Uuring era- ja avalike teenuste ruumilise paiknemise ja kättesaadavuse tagamisest ja teenuste käsitlemisest maakonnaplaneeringutes. (ENG: Tartu Ülikool RAKE (2015), Study on Spatial Location and Accessibility of Private and Public Services and Addressing Services in District Plans) https://skytte.ut.ee/sites/default/files/ec/teenuskeskuste_uuringu_lopparuanne.pdf

[11] ATAK ja Geomedia (2015), Kohalike omavalitsuste ametnike ja töötajate kompetentside kaardistamine ja koolitusvajaduse hindamise analüüs. (ENG: ATAK ja Geomedia (2015), Mapping the competencies of local government officials and employees and analysis of training needs assessment).

[12] Eesti rahvastikuprognoos 2040: neli positiivset stsenaariumi (2014). Statistikaamet (ENG: Estonian population forecast 2040: four positive scenarios (2014). Statistics Estonia) https://statistikaamet.wordpress.com/2015/10/06/eesti-rahvastikuprognoos-2040-neli-positiivset-stsenaariumi/

[13] Subnational Governments in OECD countries: Key Data, 2015 edition, OECD.

[14] Subnational Governments in OECD Countries: Key Data, 2018 edition http://www.oecd.org/regional/Subnational-governments-in-OECD-Countries-Key-Data-2018.pdf.

[16] Ladner, A., Keuffer, N. , Baldersheim, H. (2016), Measuring Local Autonomy in 39 Countries (1990–2014), Regional & Federal Studies, 26:3, 321-357.

[17] OECD (2011), Estonia: Towards a Single Government Approach, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/oecd-public-governance-reviews-estonia-2011_9789264104860-en

[18] Haldusreformi seaduse eelnõu seletuskiri (ENG: Explanatory memorandum to the draft Administrative Reform Act). https://www.rahandusministeerium.ee/sites/default/files/KOV_haldusref_maavalitsus/hrs_eelnou_seletuskiri.pdf

[19] Sootla G., Küngas G. (2007), Effects of Institutionalisation of local policymaking: A study of Central Eastern European experience, in Franzke, J., Boogers, M., Schaap, Linze (Eds), Tension Between Local Governance and Local democracy, Reed Elseiver (Business), The Hague.

[20] Sootla, G., Kattai, K., Viks, A. (2015), The size of municipalities and democracy: An institutional approach, 23rd NISPAcee Annual Conference, May 21-May 23, 2015, Tbilisi, Georgia.

[22] Viks, A. (2018), The Design of the Process of Administrative Reform, Collection of articles on administrative reform 2017 in Estonia, pp. 22-48, Ministry of Finance. https://haldusreform.fin.ee/static/sites/3/2019/01/lg_reform_eng_finale_screen.pdf

[23] Caulfield, J., Larsen, H.O. (2002), Local Government at the Millennium, Leske+Budrich, Opladen: Germany.

[24] Sepp, V., Noorkõiv, R. (2018), Central Criteria for Administrative Reform: Why stipulate 5,000 and 11,000 residents?, Collection of articles on administrative reform 2017 in Estonia, pp. 135-174, Ministry of Finance. https://haldusreform.fin.ee/static/sites/3/2019/01/lg_reform_eng_finale_screen.pdf

[25] Laan, M., Kattai, K., Noorkõiv, R., Sootla, G. (2018), Merger Negotiations Initiated by Municipal Councils, Administrative Reform 2017 in Estonia, Collection of Articles, pp 179-266. https://haldusreform.fin.ee/static/sites/3/2019/01/lg_reform_eng_finale_screen.pdf

[26] Lõhmus, M., Sootla, G., Noorkõiv, R., Kattai, K.(2018), Detsentraliseeritud valitsemis- ja juhtimiskorralduse mudelid kohaliku omavalitsuse üksustes - aasta pärast haldusreformi (ENG: Lõhmus, M., Sootla, G., Noorkõiv, R., Kattai, K. (2018), Models of decentralized governance in local government units - one year after the administrative reform). https://www.rahandusministeerium.ee/sites/default/files/KOV_haldusref_maavalitsus/osavallad_ja_kogukonnakogud_ulevaade_12.2018.pdf

[27] Viks, A. (2019), Haldusreformi käigus toimunud kohaliku omavalitsuse ametiasutuste teenistuskohtade muutused. Rahandusministeerium. (ENG: Viks, A. (2019), Changes in the places of employment of local government agencies during the administrative reform. Ministry of Finance) https://omavalitsus.fin.ee/static/sites/5/2020/02/Ametikohtade-muutus-reform.pdf

[28] Kattai, K., Lääne, S., Noorkõiv, R., Sepp, V., Sootla, G., Lõhmus, M. (2019), Peamised väljakutsed ja poliitikasoovitused kohaliku omavalitsuse ja regionaaltasandi arengus, Analüüsi lõpparuanne, Tallinna Ülikool (ENG: Kattai, K., Lääne, S., Noorkõiv, R., Sepp, V., Sootla, G., Lõhmus, M. (2019), Main challenges and policy recommendations in the development of local government and the regional level, Final Report of the Analysis, Tallinn University) https://www.riigikogu.ee/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/L%C3%B5ppraport_V%C3%A4ljakutsed-ja-soovitused-KOV-ja-regionaalarengus_31.01.2019.pdf

27 February 2026

4 березня – онлайн-лекція «Емоційний інтелект: як управляти емоціями?»

4 березня – онлайн-лекція «Емоційний інтелект:...

4 березня 2026 року о 14:30 відбудеться безоплатна онлайн-лекція «Емоційний інтелект: як управляти емоціями?» для...

27 February 2026

Language of Development Part 3: Institutions Behind EU Cohesion policy

Language of Development Part 3: Institutions...

“Language of development” is a shared voice of many — from key EU institutions to the governments of Member States,...

27 February 2026

Адміністрування податків громадами: Мінрозвитку запускає експеримент

Адміністрування податків громадами: Мінрозвитку...

Міністерство розвитку громад та територій ініціювало експериментальний проєкт, який дозволить територіальним громадам...

27 February 2026

Мінрозвитку підготував проєкт Постанови щодо...

Міністерство розвитку громад та територій України напрацювало проєкт Постанови Кабінету Міністрів «Про пріоритети...