Public investment needs at the local level in Ukraine

Howard Harding, international expert of U-LEAD with Europe

Executive Summary

The on-going decentralisation reform in Ukraine[1] has seen the formation of larger—and fewer—municipalities with increased competences. The resulting implications for public investment needs at the local level are profound, as local authorities need to ensure their new responsibilities towards a greater number of citizens. In the context of this reform, and against a background of years of under-investment,[2] this paper considers: the extent to which public investment is occurring at local level; how effective such investment is; and how much of it relates to developing the local economy. It concludes that: local investment rates meet, at most, only half the investment “demand;” planning, identifying, prioritising and ensuring equity across municipalities could be significantly improved; and investments targeting economic development are minimal. The paper closes with suggestions for policy responses that would address the findings. The primary source of evidence for the analysis is a survey of 652 local communities conducted in 2018/2019.

Introduction

This paper examines public investment at the local level in Ukraine. It is premised on the fact that such investment is not only necessary for developing communities and improving living conditions, but even for simply “standing still”: as infrastructure degrades over time, constant investment is needed for repairs and maintenance. The subject is of particular relevance in Ukraine, given the national policy of decentralisation. Initiated in 2014, this aims at the rationalisation and empowerment of local government by amalgamating numerous small local authorities into larger and fewer entities called Amalgamated Hromadas[3] (AHs), which assume key competences transferred from the national, oblast and county (rayon) levels.[4] Larger populations and expanded powers, including fiscal, entail increased responsibilities for 1) providing public service such as in health and education, and 2) developing the local economy. Continuous investment is either necessary or highly desirable in both cases: on one hand, local authorities need to ensure legally binding standards for the provision of public services, and to work towards the expectations of local residents while, on the other, they should seek to improve or at least maintain economic activity in their communities as the primary driver of material and social well-being.[5]

In line with U-LEAD with Europe’s remit, this paper’s scope is limited to Ukrainian municipalities located outside larger urban centres, which comprise “hromadas” and Cities of Oblast Significance (COSs) with a population of less than 50,000.[6] With this group of local authorities, answers are sought for three key questions:

- To what extent is public investment happening at the local level? In other words, how far do funds used for such investments go towards meeting investment needs?

- How effective is public investment at local level? Do such investments represent logically prioritised measures that will bring real benefit to the communities concerned, and are fiscal differences between these communities addressed in the interest of equity?

- To what extent do local authorities undertake investments specifically concerned with developing the local economy?[7]

Each question is addressed in dedicated sections below and is preceded by an outline of the research method and followed by a number of conclusions and pointers for policy.

For the purposes of the paper, key terms are defined as follows:

- “Public investment at the local level” means capital expenditure on physical infrastructure owned and/or operated by one or more hromadas or smaller COS. Expenditure has to meet the definition of “investment,”[8] while financing for such expenditures may be supplied by local authorities themselves, higher levels of government, donors, or even the private sector. Though investment in infrastructure owned or operated by higher levels of government is excluded, joint investments by local authorities in shared infrastructure, such as through the mechanism of inter-municipal cooperation, are possible.

- “Local economic development” (LED) initiatives are interventions undertaken by one or more hromada or smaller COS to stimulate or support private sector economic activity on its/their territory. Such interventions must target the economy directly, such as the renovation of empty premises for use by enterprises at below market rate. Initiatives undertaken for other reasons, such as social, and could lead to positive economic benefits are excluded.

The terms “(amalgamated) hromada”, “municipality,” “local authority” and “local administration” are used interchangeably.

Research approach

The evidence base for this paper comprises:

- Two original pieces of research commissioned by U-LEAD with Europe in 2018/2019: the first, a survey of 652 Amalgamated Hromadas (AHs) on investment issues and the private sector, which constitutes the primary source of data for this paper; the second, a further survey of 452 companies and self-employed individuals on their perceptions of and interest in operating outside larger urban centres;

- Analytical work performed by U-LEAD with Europe on data received from state institutions over 2019, including monitoring the financial performance of AHs, reviewing certain aspects of the State Fund for Regional Development (SFRD),[9] and modelling boundaries for prospective AHs;

- Relevant research conducted by other initiatives funded by international organisations such as SIDA.

Analysing this evidence base has made it possible to 1) extrapolate to the national level from sample data, for example, with regard to the demand for public investment at local level, and 2) identify correlations among or across data sets. Though the observations and conclusions are mostly drawn from the information received from AHs via the 2019 investment survey, they should also apply to non-amalgamated hromadas[10] and smaller COSs, since those face similar issues with regard to public investment and economic development.[11] While the underlying data is robust enough to serve as a basis for policy suggestions, it can only provide a general picture of the situation.[12] There is, therefore, a case for a more detailed and comprehensive research project.

For the most part, data is valid as of the end of 2018, while UKRSTAT figures as of January 1, 2019 have been used for population figures. Data relating to COSs with more than 50,000 residents have been excluded from samples, on the grounds that their situation is qualitatively different from that of hromadas.

Real public investment at the local level

Public investment trends at local level appear positive at first glance. For example, Levitas & Djiklic 2019 note that AHs expenditures on investment almost tripled from UAH 2.4 billion to UAH 6.9 billion between 2016 and 2018.[13] In addition, numerous state-financed grant mechanisms have been established with the specific goal of funding investment at the sub-national level to boost socio-economic development and improve infrastructure, such as roads, and health and education facilities. According to this study, grant funding under such schemes amounted to UAH 43 billion in 2018,[14] a more than four-fold increase over 2016, when the equivalent figure was UAH 8.1 billion UAH, and a not insignificant 4.3% of the national budget for that year. This upward trend is also reflected in a substantial rise in financing for state programmes concerned with territorial development, the vast majority of which address sub-national governments—from UAH 66 billion in 2018 to UAH 84 billion in 2019.[15]

Despite the increasingly large sums available, these levels are far from sufficient. Extrapolating from 2018 data, municipal spending on investment after the amalgamation process is complete would amount to some UAH 24 billion per year. Annual needs, on the other hand, are around UAH 52 billion.[16] Funding would thus fall short of demand by at least a factor of two, though this should really be treated as a significant under-estimate.[17] While the majority of this local level demand could, in principle, be met by established state programmes—for example, from the UAH 43 billion of grant funding available for the sub-national level in 2018—, in practice by far the largest share of this is directed towards oblasts and counties.[18] Further, per capita expenditure in AHs, where investment needs are increasing with increased competences, actually decreased by almost 30% between 2016 and 2018.[19] Both trends imply that the commitment to empowering local government, an integral part of the decentralisation agenda, is either rhetorical or difficult to honour politically.

How effective is local level public investment?

For public investment to be effective, it should address needs that have been 1) identified as important for the community at large, and 2) ranked in order of priority. Both of these imply some kind of medium-term planning process. At the same time, there should be a mechanism compensating for excessive disparities between different types of local authority, meaning between the “haves” and the “have-nots.”

Planning

A framework for planning investments at the local level exists in the form of Socio-Economic Development Plans (SEDPs), which set out concrete interventions in the short to medium term, based on collected/analysed data. The related guidelines were issued in 2016.[20] These plans are often supplemented by Local Development Strategies (LDSs), which cover much of the same ground, though in greater depth and over a longer timeframe.

The fact that almost every AH has an SEDP, while around two thirds have or are developing an LDS,[21] arguably shows a certain commitment to investment planning. The former are, however, de facto mandatory, since they are a requirement for accessing funding from two grant mechanisms,[22] while the latter are largely donor driven.[23] Real ownership and understanding of the planning process on the part of AHs is thus questionable: Would such plans or strategies be developed in the absence of strong external stimulus? In addition, there are doubts concerning:

- The quality of planning documents: for example, SEDPs usually cover a timeframe that is too short—1 to 2 years instead of the 3 to 5 recommended in the ministry guidelines—, while some LDSs do not contain a list of priority projects and/or do not indicate how they should be financed.

- The use of planning documents: there is no point developing a plan or strategy unless AH management follows it. It is not clear whether or not this is generally the case: Are actual investment decisions made with reference to SEDPs and LDSs?

- The overlap of SEDPs and LDSs: good planning takes time and effort, so it is not clear why AHs should be expected to conduct two very similar exercises instead of one. The added value of an LDS on top of an SEDP or vice-versa is unclear, particularly given that the ministry guidelines for both are almost identical.[24]

Identifying and prioritising investment needs

In general, interventions in social infrastructure, that is, related to the arts, sports, education, health, and social security, appear to be more commonly financed than those concerned with “hard” infrastructure like water supply, sewage and waste management. This results in smaller and more numerous projects, since investment in social infrastructure tends to be less capital intensive. There is some evidence that local authorities wish to implement larger projects,[25] something that is consistent with devoting fewer resources to social sectors apparent in the chart here. While AHs spent almost 49% on social infrastructure investments during the period covered, they intend to allocate only 38% to these sectors when it comes to their planned priority projects. The SFRD also finances social sector projects at a significantly higher rate (66%) than AHs do on their own.

Equity

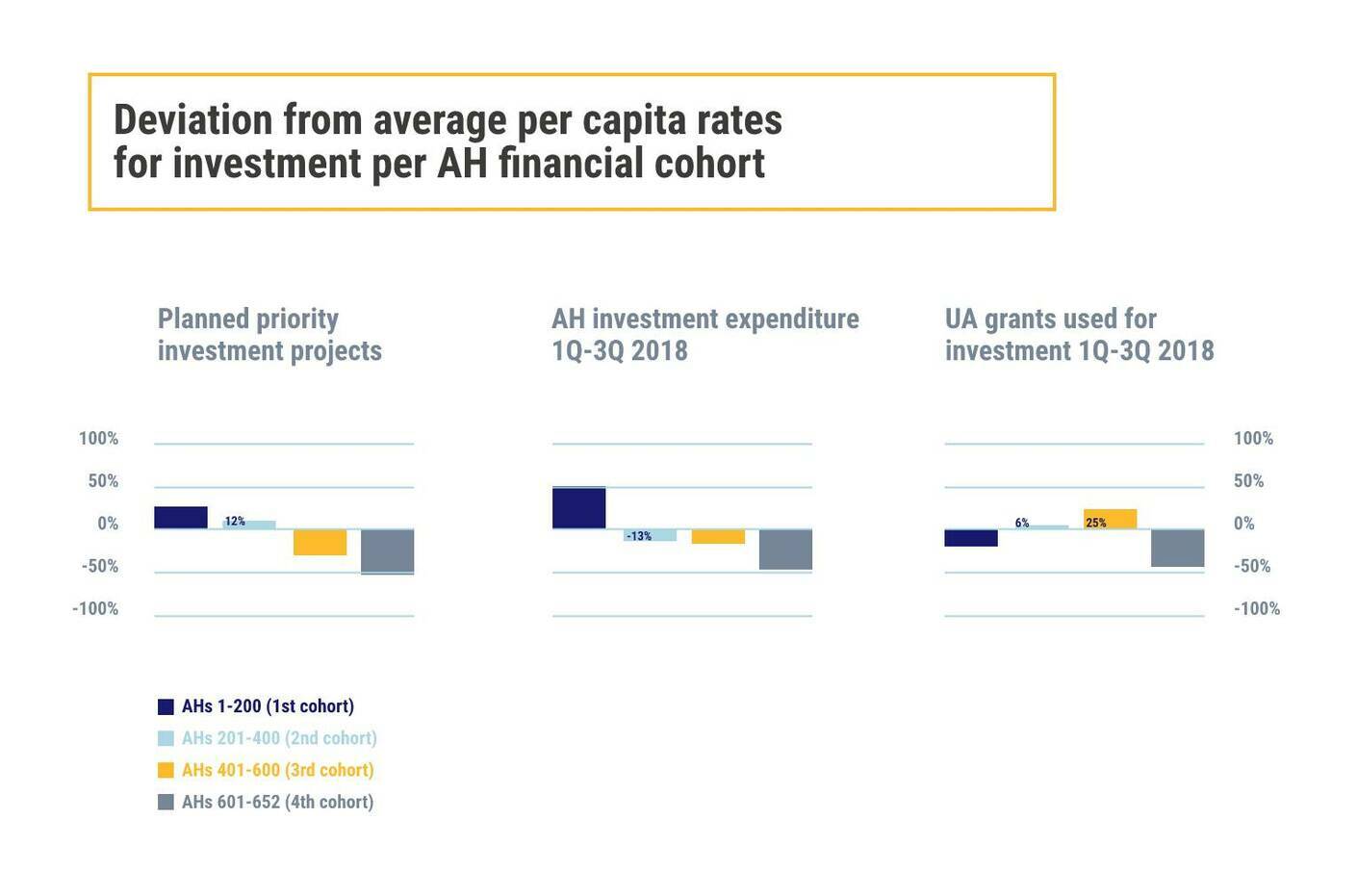

The chart here shows how much AH financial cohorts deviate from average per capita investment rates with regard to planned priority projects, investment spending, and grants received from higher levels of government (UA grants) for investment projects.[26]

While general trends are in line with expectations, that is, richer municipalities can budget and spend more per capita on investment, three issues stand out:

- AHs in the first cohort can afford to spend significantly more on investments than the rest. The gap between the 1st and 2nd cohorts, in comparison with the almost non-existent difference between the 2nd and 3rd, is noteworthy.

- In general, AHs in poorer cohorts receive proportionally more funding under Ukrainian grant mechanisms. This implies both government policy to recognise their greater needs and its application.

- The situation of the 4th cohort, the poorest, is not in line with general trends, suggesting that special attention should be paid to its AHs—roughly 10% of the survey sample. In particular, grant funding does not compensate for their limited financial situation. Indeed, they receive significantly less per capita than the 1st cohort.

A similar analysis of the same data for AHs grouped by type—urban, settlement and rural—[27] shows higher per capita investment rates and grant funding for the last category. This is congruent with what one would expect, since service provision and related investments will tend to be proportionally more expensive where population density is low, while the central government will normally operate some kind of compensatory measures.

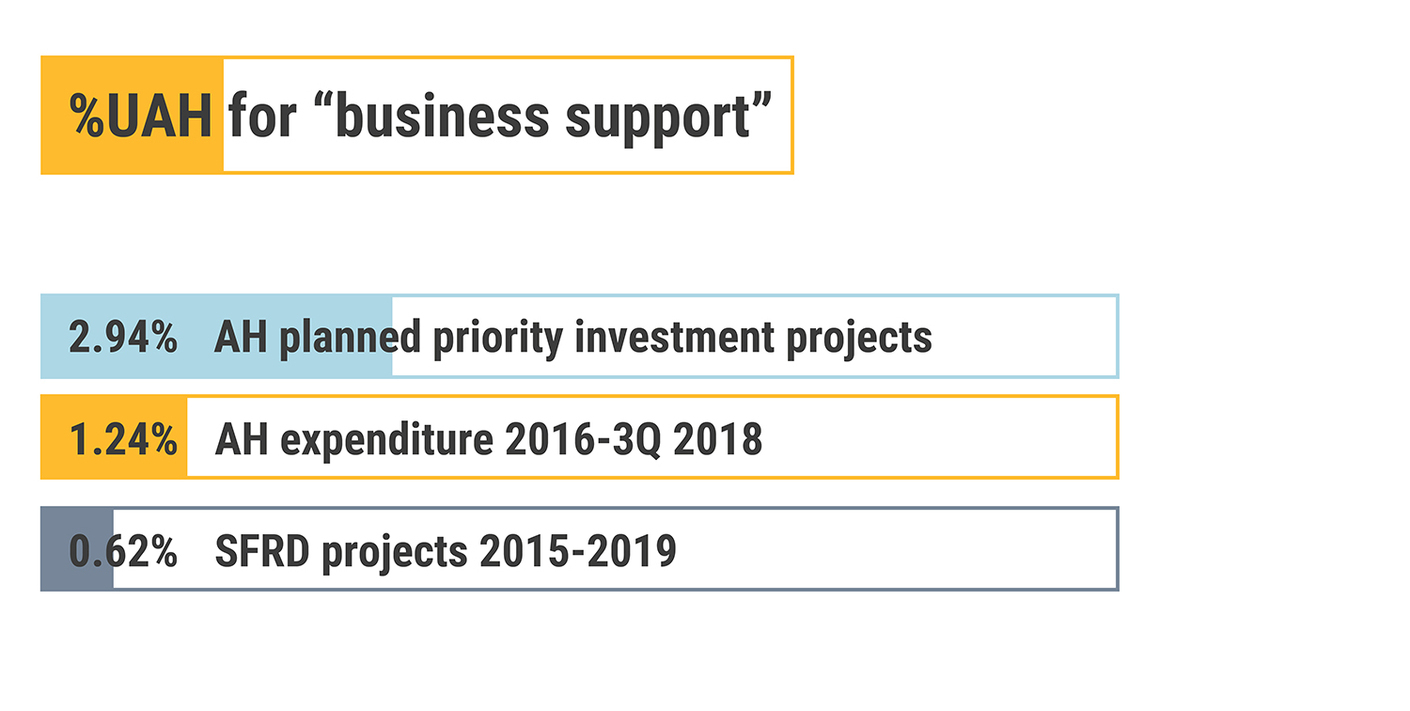

Municipal investment in Local Economic Development

Conclusions and pointers for policy

Conclusions relating to each of the three research questions are outlined here. Note that, in line with this paper’s scope, they only relate to hromadas and COSs with a population below 50,000.

1. To what extent is public investment happening at local level and how far do invested funds go towards meeting investment needs?

Reflecting the transfer of competences down to local authorities, increasing amounts have been spent on investment at local level. The sums available, however, fall far short of investment demand—by a factor of at least two. Moreover, a large proportion of new funding has been directed towards the oblasts and counties, while per capita investment rates at the local level have fallen. Both of these run counter to the decentralisation agenda’s core goal of empowering local government and this means that local administrations have seen comparatively few benefits from the massive increase in grant funding post-2016—over 300%.

2. How effective is public investment at the local level? Do such investments represent logically prioritised measures that will bring real benefit to the community? Are fiscal differences among communities addressed in the interest of equity?

While the existence of a structured planning system is viewed positively, there are doubts concerning local government ownership and use, although there is evidence of commitment on the part of local authorities.[28] The system’s complexity with effectively two planning systems[29] is also an issue.

With regard to identifying and prioritising investment needs, the central question is whether the tendency to finance smaller, more numerous investments in social infrastructure 1) represents a response to what are communities’ most pressing needs, or 2) is due to a lack of ambition and/or political considerations on the part of local administrations.[30] Here, evidence of the sensitivity of municipalities to their particular situations points to the former hypothesis.[31] Indeed, data indicate that local level investment demand is being distorted by national grant mechanisms rather than by local governments. For instance, the education sector appears to have been over-funded at local level due to the significant financing made available by the central government, and investment in social infrastructure seems to have been similarly over-funded by the SFRD.

The clear trend in poorer municipalities receiving higher grant funding for investment demonstrates the central government’s effective commitment to promoting equity among local administrations. However, the same data show that the very poorest authorities fail, for whatever reason, to benefit from this policy as, in fact, they receive less grant funding per capita than the richest municipalities.

3. To what extent do local authorities undertake investments specifically concerned with developing the local economy?

Data indicates that LED-related investment in infrastructure is very limited. Given that demands in other sectors are often more pressing,[32] it is unrealistic to expect municipalities to do otherwise. Effective LED support measures commonly require minimal or no investment, such as refitting public buildings for commercial rentals or reducing local business rates. Based on U-LEAD with Europe’s engagement with local government and private business,[33] it appears that many administrations lack a proper understanding of the private sector and fail to grasp that effective interventions are harder to design and thus turn out to be more uncertain than in other areas of public administration.[34] Despite this, a significant proportion of survey respondents expressed a desire to identify and work with potential investors, while, at the same time, enterprises in certain areas are interested in the competitive advantages of operating outside larger urban centres.[35]

Potential directions for policy, divided by research question, are drawn from this analysis and only relate to hromadas and COSs with a population below 50,000.

1. Financing for investment needs

Given Ukraine’s general fiscal situation, significant increases in funding for local level investment cannot reasonably be expected.[36] Logically, then, attention should focus on:

- Re-calibrating the balance between state resources made available to oblasts and counties and those allocated to the municipal level. Almost three quarters of grant funding reserved for the sub-national level in 2018 went to oblasts and counties. This is not in line with the core principles of the decentralisation agenda of empowering the municipal level and the assumption of new competences by local authorities requiring additional resources.

- Improving the efficiency of existing national funding mechanisms. This would primarily concern ensuring that monies allocated 1) do not remain unused, either because they were not contracted or were contracted too late to allow for full implementation, and 2) are used for their intended purposes. Here a report from the Accounting Chamber of Ukraine, the country’s top auditing institution, on the SFRD from January 2019 makes salutary reading.

2. Making public investment more effective

The system for planning investment at the local level should be re-visited with a view to streamlining. Either Socio-Economic Development Plans or Local Development Strategies should be adopted as the sole planning document. If both are retained, the added value of running two similar processes in parallel should be clarified. Some thought should also be given to the link with planning in other fields, such as spatial planning and LED. Ideally, a review of the planning system would be underpinned by research on how it is actually functioning: for example, to what extent municipalities actually follow the planning documents they have drafted and approved.

There are some signs in the data that municipalities would be more ambitious and respond more effectively to their investment needs if there were fewer limitations on funding received from higher levels of government. For example, it is very difficult to plan for larger multi-annual investments if it is not certain that the necessary grant financing will be received each implementation year. By way of illustration, U-LEAD with Europe’s survey of AHs indicates that 22% of investment expenditure at the local level depends on such grants, while the same figure for planned priority projects is 48%. This implies that a large number of initiatives will fail to see the light of day due to decisions taken at higher government levels. In order to make funding streams more predictable and allow municipalities to make investment decisions that better reflect their situation, local fiscal autonomy should be increased. In the present context,[37] the logical way to address this issue would be to move a significant proportion out of the national grant and transfer mechanisms to which conditions are attached and into the unconditional allocation each local authority receives from central government, known as equalisation grants. This would bring additional benefits: not only would it be fully in line with the principle of empowering municipalities, but it would also serve to build their administrative capacity, while reducing administrative costs and the potential for political influence associated with grant schemes.

U-LEAD with Europe survey data shows that local level capacity for preparing and implementing larger investments is limited, while, at the same time, it appears that national funding mechanisms could be better tailored to municipality needs.[38] This argues for the establishment of a central facility to:

- support local authorities with investment planning, and project preparation and implementation, particularly with regard to expanding the practice of inter-municipal cooperation;[39]

- engage in monitoring and research to inform national policy.

3. Supporting Local Economic Development

Given the typically limited capacity of municipalities in the sector, support for LED should primarily focus on:

- Measures that require no investment: Municipalities need to have an accurate picture of both the asset base—who legally owns what land parcels—and the private sector within their boundaries. They should also be familiar with and able to present their competitive advantages. Other initiatives that would benefit them include regular and effective outreach to businesses and self-employed individuals, and collaboration among neighbouring municipalities, rather than competition between them.

- Smaller investment measures: While these may concern infrastructure, such as renovating premises for commercial use, they could equally be, for example, providing small amounts of seed money to start-ups. While larger and more complex investments are possible, as a rule they should be undertaken with external technical assistance, such as from donor-funded consultants).

A central platform listing attributes of interest to business by municipality would also be helpful for linking the private sector with the local level. It is not possible at present for a furniture-maker, for example, to easily identify locations with plentiful wood resources within 50 kilometres of an oblast centre. Possible developers and hosts of such a platform would include the suggested central facility or the SME Development Office.

For further reading

Levitas, T., Djikic, J. (2019), Subnational Governance Reform and Local Government Finance in Ukraine: 2014-2018, SKL/SIDA, Kyiv – English version; Ukrainian version

Accounting Chamber of Ukraine (2019), Report on the results of the audit of the effectiveness of the use of funds of the State Fund for Regional Development, Kyiv – Ukrainian only

U-LEAD with Europe (2019), Report on the results of monitoring SFRD projects in 2015-2018 – Ukrainian only

OECD (2018), Maintaining the Momentum of Decentralisation in Ukraine,[40] OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris – English and Ukrainian versions

Copy editor: Lidia Alexandra Wolanskyj

All terms in this article are meant to be used neutrally for men and women

Howard Harding has participated at the International Expert Exchange, "Empowering Municipalities. Building resilient and sustainable local self-government", organized by U-LEAD with Europe Programme in December 2019. His speech delivered during one of the workshops is to a great extent depicted in this article. Despite its late publication, the article is still of significant relevance for the current discussion on decentralization reforms’ next steps in Ukraine.

In the name of the U-LEAD with Europe Programme, we would like to express our great appreciation and thanks for both inputs of Mr. Harding. The article will be included in future online publication Compendium of Articles.

Compendium of Articles is a collection of papers prepared by policymakers, Ukrainian and international experts, and academia after International Expert Exchange 2019 and 2020, organized by U-LEAD with Europe Programme. The articles raise questions in the fields of decentralization reform and regional and local development, relevant for both the Ukrainian and the international audience. The Compendium will be published online in Ukrainian and English languages on the U-LEAD online recourses. Please, follow us on Facebook to stay informed about the project.

If you have any comments or questions about the Compendium of articles or this article in particular, please contact Yaryna Stepanyuk yaryna.stepanyuk@giz.de.

[1] Please, note that the article was finalized in early 2020 and depicts situation in the country as of that time. In this way, the term ‘amalgamated hromada’ is being used.

[2] As noted in “Maintaining the Momentum of Decentralisation in Ukraine” p.183, “Fixed capital stocks in the public sector are ageing and of mediocre quality, and the country’s infrastructure needs are tremendous.”

[3] As of October 2020, they are called simply municipalities.

[4] As of September 2020, 983 Amalgamated Hromadas were formed out of a planned total of 1,469, down from the almost 12,000 communities prior to the reform.

[5] Investment in infrastructure that keeps existing businesses in a community, helps them to grow, or attracts new ventures, should result in an increase in the economic output generated. In turn, this should lead to material benefits both for individuals, in the form of higher wages and improved living conditions, and the community at large, in the form of increased revenue from taxes and greater autonomy with regard to setting priorities and related expenditures. Social benefits should also flow from economic development: earning a wage gives an individual a sense of agency and a feeling of self-worth, while communities will generally be more socially cohesive the more residents feel they have a stake in the local economy.

[6] Under Ukrainian law, the basic administrative/territorial units comprise the City of Kyiv, “cities of oblast significance” and “hromadas.” Although COSs are mostly designated on the basis of population, other factors are also taken into account, including cultural or historical significance. As a result, of the 151 current COSs (not including those in the Temporarily Occupied Territories), over 50% have a population of less than 50,000. Hromadas are divided into urban, rural and settlements, that is, population centres in between urban and rural.

[7] Particularly relevant for hromadas, many of which have seen a significant proportion of the working age population relocate to urban centres for lack of economic opportunities locally.

[8] That is, rather than simple disbursement of available funds for public goods, it needs to aim at realising economic and/or social returns that should outweigh the initial inputs.

[9] The SFRD is the primary non-sectoral national grant mechanism for financing investment projects proposed by, among others, sub-national governments. In 2019, it was allocated UAH 7.67 billion.

[10] Note that the distinction between amalgamated and non-amalgamated hromadas disappeared, as the latter transitioned to the former, in line with the progress of decentralisation reform.

[11] By contrast, the paper is less relevant to larger COSs, given the qualitative difference in their situation, compared to hromadas: high population density, a well-developed built environment, ready access to higher level public services and amenities, a mixed and sizeable economy, good transport links, and higher administrative capacity.

[12] This is mainly due to the fact that, at the time the key survey addressing AHs was conducted, they covered far less than 50% of the geographical area and population outside urban centres. Moreover, their number in each oblast varied so greatly that meaningful comparisons across regions were not possible.

[13] See “Subnational Governance Reform and Local Government Finance in Ukraine: 2014-2018,” Table 6, p 30.

[14] See Levitas & Djikic 2019, Chart 4, p 14.

[15] See “Державна підтримка розвитку територій”, p 3; in Ukrainian only.

[16] Aggregate expenditure is calculated by multiplying the annual per capita amount spent on investment by AHs in 2018, UAH 1,229 (see Levitas & Djikic 2019, Table 6, p 30), by the population (UkrStat data for January 1, 2019) forecast for municipalities after the completion of the amalgamation process—based on plans valid at the end of October 2019, with modelling of areas where boundaries had yet to be agreed. Aggregate needs are estimated similarly, though in this case, the per capita amount was derived from the 2,323 priority project ideas received in response to U-LEAD with Europe’s investment survey of AH. These project ideas served as a proxy for realisable investment needs over a two-year horizon. Note that aggregate figures exclude: 1) COSs with populations exceeding 50,000 and the City of Kyiv; and 2) the Temporarily Occupied Territories.

[17] Since the per capita rate used to estimate investment needs is based on 1) responses from AHs that formed earlier and are therefore likely to be richer (see Levitas & Djikic 2019, p 32), and thus have fewer investment needs; and 2) ideas for priority projects, excluding expenditure necessary for smaller investments, such as maintenance and repairs.

[18] For example, 74% of grant funding available at the sub-national level in 2018 was allocated to oblasts and counties. See Levitas & Djikic 2019, Table 2, p 15.

[19] See Levitas & Djikic 2019, Table 6, p 30.

[21] As of the end of March 2019, 37% of AHs had an LDS, while 28% were developing one.

[22] For infrastructure in AHs and socio-economic development at the local level.

[23] Over 70% of LDSs at end 2018 were developed with donor support, such as EU-funded U-LEAD with Europe, USAID-financed DOBRE and Polish Aid.

[24] In addition to the formal guidance on SEDPs issued in 2016, a document relating to LDSs was posted in 2018 (see https://decentralization.ua/news/9514).

[25] For example, the median value of AH planned priority projects is UAH 4 million, with 25% above UAH 10 million. The same figures for projects financed under the SFRD between 2015 and 2019 are UAH 1.44 million and 12%.

[26] Experts from U-LEAD with Europe and SKL International (http://sklinternational.org.ua) monitor AHs against three financial indicators—revenue per capita, amount of equalisation transfer, expenditure on AH operational costs—on an annual, bi-annual or quarterly basis. For the most recent such monitoring at the time of writing, see https://decentralization.ua/news/12783 (in Ukrainian only). Each AH is ranked in line with its performance against each indicator, as well as overall. The 652 AHs surveyed by U-LEAD are grouped into 4 “cohorts” based on their overall ranking for fiscal year 2018, which is used as a proxy for wealth.

[27] AHs can be grouped by any number of criteria, such as population, geographical area, and so on. Though the division into urban, settlement and rural is somewhat arbitrary, as the Act designating the divisions dates from the 1980s, it does generally tend to follow the most important factor determining the demand/supply of public services and related infrastructure—population density.

[28] Around 30% of LDSs were initiated and drafted by AHs on their own, rather than at the instigation of donors.

[29] One for SEDPs, and a second for LDSs.

[30] Note that there is a “natural” tendency towards such projects, given that they are easier to prepare, finance and implement than larger investments in “hard” infrastructure such as water supply or sewage.

[31] Data from the investment survey of AHs clearly showed logical correlations between AH types and previous/planned expenditure per sector. For example, investment in public safety infrastructure was much more common in rural Ahs, given the distance to the nearest fire or police station, while large infrastructure, such as sewage, was much more relevant for urban AHs.

[32] They often relate to statutory responsibilities ensured by municipalities. This is not the case with investment demands in the business sector.

[33] For example, working with a number of AHs to develop projects to attract investors.

[34] Successful investment in infrastructure in most sectors simply requires accurate engineering. Success with business support, however, depends on the response of the target audience—will investors re-locate?—something that is much less predictable.

[35] Competitive advantages include large amounts of unused and cheap space, agriculturally productive land and a workforce, and certain raw materials, such as wood. Examples of businesses that might be interested in operating in such communities include logistics and storage companies, fruit/berry processors, and producers of solar energy and furniture-makers.

[36] In this context, the central government has never been able to meet the legal obligations for financing the SFRD, whose annual allocation should be no less than 1% of the General Fund of the State Budget. Still, each successive year has seen an improvement, with 83% of the SFRD’s mandate financed 2019, compared with 53% in 2016.

[37] There are other ways of increasing the fiscal autonomy of municipalities, such as by increasing their tax-raising powers.

[38] For example, apparent over-funding in the education sector points to an imbalance between central government policy and local level needs.

[39] Many public services falling under the responsibility of local administrations are delivered more efficiently if resources are pooled across several—usually contiguous—jurisdictions. Inter-municipal cooperation is a mechanism that allows such pooling, but it requires mutual trust and sensitive negotiation, and should result in fair contractual terms for all parties. Encouragingly, 18% of planned priority projects identified by AHs surveyed foresaw inter-municipal cooperation. However, contracts had only been concluded for 4% of them. It is also apparent that inter-municipal cooperation is occurring throughout Ukraine, though it tends to be geographically concentrated, such as in Poltava Oblast. See monthly reporting on indicator 5 of the decentralisation process at https://decentralization.ua/mainmonitoring#main_info (in Ukrainian only).

[40] In particular Chapter 3

Tags:

expertnotes international experience

Source:

U-LEAD with Europe

20 February 2026

Місцева статистика: Як перетворити розрізнені...

У Києві відбулася стратегічна зустріч "Статистика громад", організована Державною службою статистики України за...

20 February 2026

I_CAN launched a nationwide rollout of its Public Investment Management Training Programme for local governments and...

20 February 2026

Language of Development Part 2: Funds and Instruments of EU Cohesion Policy

Language of Development Part 2: Funds and...

With the “language of development”, we describe not only the goals and principles of EU regional policy, but also...

19 February 2026

Анонс: вебінар «Обговорення змін до Порядку...

Які практичні кроки мають здійснити керівники та педагоги, щоб ефективно впровадити ключові зміни до Порядку...