How jurisdiction size relates to good local governance

Dr. Felix Roesel is an economist at the ifo Institute in Dresden, Germany.

Dr. Felix Roesel is an economist at the ifo Institute in Dresden, Germany.

His research focuses on local government, democratic participation, and urbanisation.

Executive summary

Eastern Germany rigorously reduced the number of municipalities from 12,500 to less than 2,500. The central government expected significant economies of scale, cost savings, and professional services in the amalgamated jurisdictions. But after large and widespread protests in 2017, amalgamations came to a halt. Tens of thousands of Germans rallied, worried that further amalgamation reforms would produce oversized municipalities and that control over local affairs would fade away. Ultimately, the central government cancelled all plans for forced amalgamations in the light of ever-growing protest and surging populist votes in national elections.

The protests in eastern Germany contributed to a critical debate on the optimal jurisdiction size that might deliver best on good local governance. This article analysed this issue in light of some 30 years of amalgamation reforms in eastern Germany. It turns out that size has an ambiguous role. On one hand, large local governments professionalise and do have the capacity to operate at costs efficient levels—and their new decentralised tasks require such capacities. On the other, smaller jurisdictions are superior in tailoring policies to local needs because they are closer to local communities. New evidence shows that oversized eastern German municipalities have become unmanageable, communication between local administrations and residents have suffered, local identity has eroded, and interest in local affairs has faded away.

The implications for Ukraine’s case are that scaling new municipalities should carefully trade off the technical needs of administrative capacities, on one hand, and foster local democracy, on the other, in order to take advantage of the huge potential of decentralisation. The optimal size carefully balances three aspects of good local governance: administrative capacity, manageability and participation.

Following a brief background, the body of this article first briefly introduces the methods and data used in the empirical part. Next it describes 30 years of local government amalgamations in eastern Germany and lessons for Ukraine’s reform. Finally, some first evidence on municipality size and participation in local elections is presented and the conceptual framework for deriving the “optimal size” is described as a conclusion.

Context and background

Local boundaries can raise strong emotions. In spring 2017, some eastern German cities saw the biggest political rallies since the famous “Monday demonstrations” of 1989, when people marched against the communist regime. Figure 1 is a snapshot of the protests in the city of Sonneberg, where thousands gathered at the market square. Protests were directed against central government plans for the forced amalgamation of local governments. More and more citizens rallied, filed petitions, and supported direct democratic initiatives. Polls revealed that 69% of the eastern Germans opposed new amalgamation reform, and only 25% supported the proposal.[1] After months of ever-growing protest and surging populist votes in national elections, the central government cancelled all plans for forced amalgamation in late 2017.

Figure 1: Anti-amalgamation protest in eastern Germany, May 2017

The anti-amalgamation rally on May 8, 2017 in the city of Sonneberg. Source: The Sonneberg County Administration (Landratsamt Sonneberg, Michael Volk).

Rescaling local administrations is not unique to eastern Germany. Many other countries in Central and Eastern Europe have implemented similar local government reforms since the fall of the Iron Curtain: Bulgaria, Estonia and Latvia all amalgamated local governments. Amalgamations have usually been coupled with new administrative tasks delegated to the new local governments.[2] The rationale of the current decentralisation reform in Ukraine illustrates this idea well: the newly-formed municipalities come along with new responsibilities. Decentralising public services to local governments empowers communities and brings decision-making closer to voters. This can make public monitoring of politicians easier, increase accountability, and facilitate trust towards administrations and politicians.

So, what went wrong that tens of thousands of eastern Germans rallied against amalgamation reforms in 2017? The basis for the protests was the nature of amalgamation in eastern Germany, which was different from many other countries. Since 1990, Germany’s central government continually redrew local boundaries—sometimes year after year. This caused considerable and growing uncertainty. Many amalgamations were designed top-down and included forced mergers.

Most importantly, eastern German amalgamation reforms involved hardly any actual decentralisation. The upscaling was almost entirely motivated by the technical aspects of administrative capacity: economies of scale, cost savings and service efficiency. Amalgamations in eastern Germany often simply aimed at maximizing population numbers, based on the principle, the bigger, the better. This strategy was supported by many experts from administrative sciences but came to a sudden halt in mid-2017, when tens of thousands of eastern Germans rallied for smaller local governments. People worried that further amalgamation reforms would lead to oversized municipalities and that control over local affairs could fade away. Thus, eastern Germany is a rather exceptional opportunity for research, to separate the effects of changes in jurisdiction size from aspects of decentralisation that often overlap in many other countries.

In this article, the specific nature of amalgamation reforms in eastern Germany is the basis for studying how local government size influences different aspects of the quality of its governance. The main focus looks to the “soft” factors of good local governance addressed by the protests in eastern Germany. These have essentially not been covered in many debates on amalgamation reforms so far: proximity, responsiveness and civic participation. Key findings of the related studies surveyed in this article show that size has a more ambiguous role in good local governance than previously acknowledged. Large local governments may have the capacity to operate at cost-efficient levels, while smaller jurisdictions are superior in tailoring policies to local needs because such governments are closer to their local communities. Amalgamations eliminated more than 80,000 of the 120,000 original seats on local councils, leaving hundreds of eastern German villages without political representation at any level of government. As a consequence, studies have shown that voter turnout, the number of candidates in local elections, and local identity have all declined since larger municipalities were established, while populist tendencies have surged.

Since 2014, Ukraine has been developing new and empowered structures of subnational government. A key element of the reform is to transfer powers and resources, mainly in healthcare and education, to local governments that have voluntarily amalgamated and formed new municipalities.[3] Decentralisation and amalgamation go hand-in-hand to make sure that new responsibilities are provided with adequate administrative capacities. However, early evidence from the new Ukrainian municipalities presented in this article shows parallels with the eastern German experience, with higher voter turnout in smaller municipalities.

The role of jurisdiction size

Methods and data

This article combines a comprehensive review of literature with new analyses of both German and Ukrainian local election data. First, high-quality studies evaluating the amalgamation reforms in eastern Germany are summarized. The main focus is on the effects of jurisdiction size on the local decision-making process, participation and local democracy. The best available evidence comes from studies that compare amalgamated municipalities to a control group of unchanged municipalities, before and after amalgamations. This quasi-experimental study design makes it possible to separate the causal impact of jurisdiction size from other effects. The eastern German experience is complemented with evidence from other countries, mainly in Central and Eastern Europe.

Second, new election data from Ukrainian and eastern German municipalities is applied. Two datasets have been assembled and voter turnout in the first elections in Ukrainian municipalities is compared with election results in amalgamated eastern German municipalities in the federal state of Thuringia. The hypothesis is that jurisdiction size influences political participation in both countries. Whether jurisdiction size comes with differences in voter turnout in local elections is then tested. The data is reported in scatter plots and in simple statistics. To make the results comparable across countries, the samples are limited to 197 Ukrainian and 162 eastern German amalgamated municipalities with less than 10,000 eligible voters. Local elections were held in 2018 or 2019 in the two countries. Eastern German data comes from the Thüringer Landesamt für Statistik, the statistical agency of the German state of Thuringia), while Ukrainian data was collected and provided by U-LEAD with Europe.

The eastern German experience

Background

Amalgamation reforms have eliminated more than 10,000 municipalities in eastern Germany since World War II. The number of local governments went from 12,500 in 1946 to 7,500 in the communist era by 1989-1990, and permanent amalgamation reforms after re-unification reduced the number of local governments much further, to less than 2,500. Mergers were voluntary, “semi-voluntary” due to compelling financial incentives, and often also forced. They usually included minimum population and maximum area targets for new municipalities. Today, the average eastern German municipality has an average of 5,200 residents, while the area has expanded to an average of 45 square kilometres, excluding Berlin. Fully 98% of all municipality amalgamations in Germany between 1990 and 2020 took place in the eastern part. Hardly any municipalities were amalgamated over this period in western Germany.

Amalgamation reforms were mainly motivated by the rapid decline of eastern German population numbers: eastern Germany lost 5 million mainly young inhabitants since 1946 and is now back only to 1905[4] levels. Western Germany, by contrast, has grown by more than 20 million since WWII. The reasoning behind territorial-administrative reforms came from arguments by experts that the administration of shrinking and aging municipalities in eastern Germany would not be able to operate at efficient levels in the future. Larger administrations are typically more specialized and capable of handling complex tasks. However, decentralisation hardly played a role. In contrast to the ongoing Ukrainian reform, only few additional tasks were delegated to eastern German municipalities, which already enjoyed a great deal of autonomy. Amalgamations in eastern Germany purely aimed at cost savings, growth, efficiency and better services. Some central governments expected tremendous savings, estimated at 10-30%, in local operating costs.

Economic effects

Amalgamations in eastern Germany had a clear economic purpose. However, evaluations conducted in recent years have shown that upscaling municipalities in eastern Germany often failed to deliver improved local budgets and economic growth. The evidence shows that those original estimations of cost savings were far too optimistic. Any cost savings that were achieved were mainly limited to small municipalities:

- Costs: For tiny eastern German municipalities, studies have shown some savings in administrative expenditures after amalgamation[5] while amalgamations of already large local governments hardly cut any costs.[6] Recent literatures, including a multi-country perspective, corroborate the eastern German experience: scale effects in local government are mainly limited to administrative expenditures, which are only a small fraction of public spending.[7]

- Growth: Amalgamation was not found to spur economic growth in amalgamated eastern German municipalities, while economic activities relocated a great deal. Jobs, income and inhabitants concentrate more in the centres.[8] Former capital cities in eastern Germany lost large shares of their original population after local administrations were lumped together in a new centre, with thousands of relocated public servants moving from rural to urban regions.[9]

- Efficiency: So far, no study examined for this article has evaluated whether amalgamation has changed administrative efficiency or capacities in eastern Germany. However, small eastern German municipalities were found to operate efficiently even before reforms because many operated as joint administrations.[10] Evidence from Switzerland shows that amalgamation has limited impacts on self-assessed administrative performance limits.[11] Other surveys confirm that the evidence on the size-efficiency nexus is inconclusive.[12]

Political effects

The economic aspect dominated the discourse on amalgamation reforms in eastern Germany. Political aspects played only a minor role. However, amalgamation cut back not only the bureaucracy, but also opportunities to participate. More than 120,000 citizens volunteered as local councillors after the first democratic local election in early 1990. Three decades of municipality amalgamations later, only about 37,000 council positions remained. Resizing had substantial effects on the roots of democracy and the “soft” factors of good governance:

- Representation. Amalgamations in eastern Germany eliminated three out of four unsalaried seats in local councils since 1990. Today, many eastern German municipalities have more villages than local councillors, leaving hundreds of communities without political representation at any level of government. Evidence from the Czech Republic has shown that populous regions dominate in amalgamated local councils.[13] Many problems and voices from rural villages go unheard as the urban-rural gap widens.

- Identity. One out of four eastern Germans has lost their local identity after amalgamation reforms.[14] Protesters waved local flags and coats of arms in the spring of 2017, when tens of thousands rallied against forced amalgamation in eastern Germany. Local identity is not only about folklore: it has been found to be an important pre-condition for participation, volunteering and tolerance in eastern Germany.[15] “Uprooted” voters also tend to be more susceptible to populism. Vote shares for populist parties have increased in amalgamated eastern German municipalities.[16]

- Manageability. Large jurisdictions are difficult for both local politicians and voters to handle. A Danish study shows that the complexity of local politics increases in large jurisdictions.[17] Often, only professional politicians are able to cope with the increasing workload in amalgamated municipalities. Accordingly, the number of candidates in local elections in eastern Germany has declined since amalgamations.[18] As monitoring local politics becomes more difficult, residents in Danish amalgamated municipalities feel less informed about local affairs. Trust and satisfaction with local politicians and the administration go down.[19]

- Participation. Size reduces representation, identity and also participation. Studies from many countries have all consistently shown that voter turnout in local elections goes down after amalgamation, in eastern Germany and elsewhere.[20] The impact of a single ballot on the ultimate election outcome is much larger in a community of 50 than in a town of 50,000. A series of studies confirms that participation in local elections is lower in larger jurisdictions.[21]

In conclusion, amalgamation reforms in eastern Germany aimed at an economic impact, but mainly resulted in unanticipated and unexpected political side-effects. Heads of local governments have to handle very large administrations with thousands of employees. Today, one local councillor has to bear the workload of four councillors in 1990 when serving municipalities with 50 and more villages. Amalgamated local governments in eastern Germany may now operate somewhat more cost efficiently, but officials don’t always have a proper sense of genuine local needs. The distance between local voters and local politics has grown, and voter turnout has declined.

The Ukrainian experience

One of the first observable outcomes of Ukraine’s decentralisation reform is voter turnout in local elections. If residents are more interested in local affairs, they are more likely to cast a ballot and voter turnout goes up. In contrast to eastern Germany, decentralization and amalgamation have gone hand-in-hand in Ukraine. Both aspects of the reform can influence voter turnout. On one hand, decentralisation empowers local communities, so voter turnout is likely to increase if local responsibilities grow significantly. On the other, an individual ballot matters less in larger communities than in smaller communities, leading to lower turnout levels. This is what the eastern German experience and causal evidence from many other countries have shown. This suggests that, Ukrainian decentralisation reform could result in an overall increase in voter turnout in new municipalities, with significant differences between smaller and larger municipalities. Data from the 2020 local elections not being available at the time of writing, only the effect of size within the group of new municipalities can be investigated, compared to the results from eastern Germany.

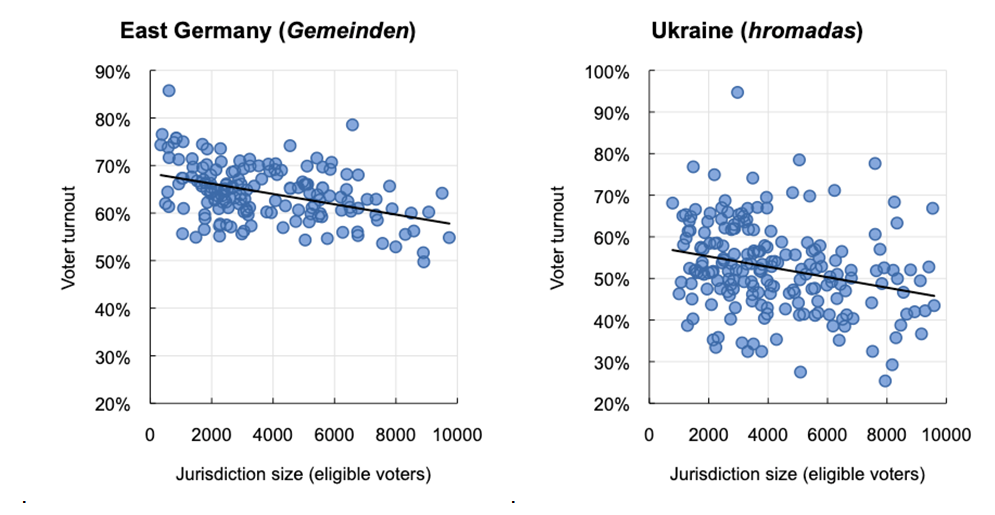

Figure 2 includes 162 amalgamated municipalities or Gemeinden in eastern Germany on the left-hand side and 197 newly-formed Ukrainian municipalities on the right-hand side. Each dot represents an amalgamated municipality with less than 10,000 eligible voters. The vertical axis depicts the share of voters turning out to the polls in local elections in 2018 or 2019, while the number of eligible voters stands for the jurisdiction size and is the horizontal axis. The results show that voter turnout varies more across Ukrainian municipalities than across eastern German ones. On average, voter turnout is actually somewhat higher in eastern German municipalities than in Ukrainian ones. Despite those differences in levels, the relationship between size and voter turnout is strikingly similar in both countries: the larger the amalgamated municipality, the lower voter turnout in local elections. The slope of the regression that marks the size of the effect is comparable: 1,000 more eligible voters match a decrease in voter turnout of around 1% in both countries.[22] This negative correlation is in line with a growing number of studies documenting the negative causal relationship between size and participation in local elections. Unfortunately, pre-reform turnout rates are not available to compare the effects of amalgamation to the effects of decentralisation. Decentralisation may have increased turnout in all communities, but especially in smaller municipalities.

Figure 2: Voter turnout and size of amalgamated municipalities

Source: Thüringer Landesamt für Statistik (Statistic agency of the state of Thuringia), U-LEAD with Europe

Notes: The figures compare jurisdiction size or the number of eligible voters to voter turnout or the share of eligible voters actually voting in local elections in 162 amalgamated eastern German municipalities (left) and 197 Ukrainian municipalities (right). Elections were in either 2018 or 2019.

Conclusion. Main findings

The residents of a community expect professional public services. Larger administrations are typically more specialized and able to handle complex tasks. This does not, however, mean that a country should simply maximize the size of municipalities. The main takeaway from 30 years of permanent amalgamation reforms in eastern Germany is that administrative capacity is only one aspect of good local governance. Good local governance equally requires local knowledge, responsiveness and the involvement of locals. Large administrations may operate at somewhat lower costs and higher quality, but smaller jurisdictions are better able to tailor policies to meet local needs. Local boundaries also affect emotions, identity and democracy. If too many overly heterogeneous local governments are lumped together, the urban-rural gap expands, representation and participation shrink, and populism rises.

Ukraine’s decentralisation reform is a great opportunity, provided that the new municipalities carefully trade off the technical needs of administrative capacities and local democracy. In contrast to eastern Germany, where the central government established large new local jurisdictions, in Ukraine the scaling of new municipalities is in the hands of local decision-makers. This makes it possible to redraw boundaries that really meet local needs and preferences. Unfortunately, there is no easy rule of thumb for resizing local governments. Figure 3 illustrates the trade-offs of amalgamation reforms that need to be considered to ensure good local governance, carefully balancing administrative capacity, manageability and participation. The optimal size of municipalities may well differ across the country, depending on the weight local communities assign to the criteria. In any case, three decades of amalgamation reforms in eastern Germany have shown that focusing on administrative capacity alone can jeopardize the benefits of decentralisation.

Figure 3: Criteria for good local governance

|

Good local governance |

||

|

Administrative capacity |

Manageability |

Participation |

|

Costs, growth, |

Local knowledge, proximity, responsiveness |

Identity, democracy, involvement in local affairs |

|

Increases in size |

Decreases in size |

Decreases in size |

Source: Author illustration

Further readings

- A 2019 special issue on Municipal Amalgamations of Local Government Studies #45(5) includes several interesting case studies of amalgamation reforms and summarizes recent academic literature. Access at: https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/flgs20/45/5?nav=tocList

- If physical distances and municipality size grow a lot, apps and web interfaces become valuable shortcuts to local communities. Prominent examples are “Open Budgets” (https://openbudgets.eu/) or “Smarticipate” (https://www.smarticipate.eu/), which several EU cities have successfully adopted.

- The potentials of intermunicipal cooperation that allows selective collaboration among two or more smaller local governments can be used to advantage, with all political powers remaining with the partners: https://www.coe.int/en/web/good-governance/imc-eap

Note: All hyperlinks were finally checked in August 2020.

Copy editor: Lidia Alexandra Wolanskyj

All terms in this article are meant to be used neutrally for men and women

Dr. Felix Roesel has participated at the International Expert Exchange, "Empowering Municipalities. Building resilient and sustainable local self-government", organized by U-LEAD with Europe Programme in December 2019. His speech delivered during one of the workshops is to a great extent depicted in this article. Despite its late publication, the article is still of significant relevance for the current discussion on decentralization reforms’ next steps in Ukraine.

In the name of the U-LEAD with Europe Programme, we would like to express our great appreciation and thanks for both inputs of Dr. Roesel. The article will be included in future online publication Compendium of Articles.

Compendium of Articles is a collection of papers prepared by policymakers, Ukrainian and international experts, and academia after International Expert Exchange 2019 and 2020, organized by U-LEAD with Europe Programme. The articles raise questions in the fields of decentralization reform and regional and local development, relevant for both the Ukrainian and the international audience. The Compendium will be published online in Ukrainian and English languages on the U-LEAD online recourses. Please, follow us on Facebook to stay informed about the project.

If you have any comments or questions about the Compendium of articles or this article in particular, please contact Yaryna Stepanyuk yaryna.stepanyuk@giz.de.

This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union and its member states Germany, Poland, Sweden, Denmark, Estonia and Slovenia. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of its authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the U-LEAD with Europe Programme, the government of Ukraine, the European Union and its member states Germany, Poland, Sweden, Denmark, Estonia and Slovenia.

[1] Märkische Oderzeitung, Umfrage: Brandenburger lehnen Kreisreform ab, 02.12.2016, https://www.moz.de/nachrichten/brandenburg/umfrage_-brandenburger-lehnen-kreisreform-ab-48695942.html Access: February 11, 2020; Kommunal.de, Gebietsreformen bringen Unmut, 23.12.2016, https://kommunal.de/gebietsreformen-bringen-unmut, Access: February 11, 2020.

[2] For an overview, see Swianiewicz, P., Gendźwiłł, A., and Zardi, A. (2017), Territorial reforms in Europe: Does size matter? Centre of Expertise for Local Government Reform, Council of Europe, Strasbourg.

[3] The reform also includes reorganising counties (rayons). For institutional details on the Ukrainian reform, see OECD (2018), Maintaining the Momentum of Decentralisation in Ukraine, OECD Publishing, Paris; Dudley, W. (2019), Ukraine’s decentralization reform, SWP Working Paper, Research Division Eastern Europe/Eurasia 1; Umland, A., and Romanova, V. (2019), Ukraine’s Decentralization Reforms Since 2014: Initial Achievements and Future Challenges, Chatham House Research Papers.

[4] The local eastern German population dips to lowest level in 114 years, December 6, 2019. https://www.thelocal.de/20190612/eastern-german-population-dips-to-lowest-level-in-114-years Access: February 11, 2020.

[5] Blesse, S., and Baskaran, T. (2016), “Do municipal mergers reduce costs? Evidence from a German federal state,” Regional Science and Urban Economics, #59, pp 54-74.

[6] Roesel, F. (2017), “Do mergers of large local governments reduce expenditures? Evidence from Germany using the synthetic control method,” European Journal of Political Economy, #50, pp 22-36; Blesse, S., and Roesel, F. (2019), “Merging county administrations: Cross-national evidence of fiscal and political effects,” Local Government Studies, #45(5), pp 611-631.

[7] Tavares, A. F. (2018), “Municipal amalgamations and their effects: A literature review,” Miscellanea Geographica, #22(1), pp 5-15; Gendźwiłł, A., Kurniewicz, A., and Swianiewicz, P. (2020), The impact of municipal territorial reforms on the economic performance of local governments. A systematic review of quasi-experimental studies, Space and Polity, forthcoming.

[8] Egger, P., Köthenbürger, M., and Loumeau, G. (2017), Local border reforms and economic activity, CESifo Working Papers, 6738.

[9] Heider, B., Rosenfeld, M. T., and Kauffmann, A. (2018), “Does administrative status matter for urban growth? Evidence from present and former county capitals in East Germany,” Growth and Change, #49(1), pp 33-54. Evidence from amalgamation reforms in Japan and Norway corroborates the increase in the urban-rural gap after amalgamations because of centre-dominated administrative expenditures and staff relocation. Pickering, S., Tanaka, S., and Yamada, K. (2020), “The impact of municipal mergers on local public spending: evidence from remote-sensing data,” Journal of East Asian Studies, #20(2), pp 1-24; Harjunen, O., Tuukka, S., and Tukiainen, J. (2019), Political representation and effects of municipal mergers, Political Science Research and Methods, forthcoming.

[10] Bönisch, P., and Haug, P. (2018), “The Efficiency of local public-service production: The effect of political institutions,” FinanzArchiv: Public Finance Analysis, #74(2), pp 260-291.

[11] Steiner, R., and Kaiser, C. (2017), “Effects of amalgamations: Evidence from Swiss municipalities,” Public Management Review, #19(2), pp 232-252.

[12] Narbón Perpiñá, I., and De Witte, K. (2018), “Local governments' efficiency: A systematic literature review—part II,” International Transactions in Operational Research, #25(4), pp 1107-1136.

[13] Voda, P., and Svačinová, P. (2020), “To be central or peripheral? What matters for political representation in amalgamated municipalities?” Urban Affairs Review, #56(4), pp 1206-1236.

[14] Foertsch, M., and Roesel, F. (2020), “Territorial reforms reduce sense of local identity,” https://www.ifo.de/en/publikationen/2020/article-journal/territorial-reforms-reduce-sense-local-identity Access: February 11, 2020.

[15] Foertsch, M., and Roesel, F. (2020), “Volunteering and tolerance need local roots.” https://www.ifo.de/en/publikationen/2019/journal-complete-issue/ifo-dresden-berichtet-62019 Access: February 11, 2020.

[16] Roesel, F. (2017), “Do mergers of large local governments reduce expenditures? – Evidence from Germany using the synthetic control method,” European Journal of Political Economy, #50, pp 22-36; op. cit., Blesse, S., and Roesel, F. (2019).

[17] Loftis, M., Mortensen, P., Seeberg, H., and Serritzlew, S. (2020), Jurisdiction size and the nature of political discussion: Quasi-experimental evidence on scope, content and complexity of political discussion in 98 municipalities, unpublished Working Paper.

[18] Op. cit, Roesel, F. (2017)

[19] Lassen, D. D., and Serritzlew, S. (2011), “Jurisdiction size and local democracy: Evidence on internal political efficacy from large-scale municipal reform,” American Political Science Review, pp 238-258; Hansen, S. W. (2013), “Polity size and local political trust: A quasi-experiment using municipal mergers in Denmark,” Scandinavian Political Studies, #36(1), pp 43-66; Hansen, S. W. (2015) “The democratic costs of size: How increasing size affects citizen satisfaction with local government,” Political Studies, #63(2), pp 373-389.

[20] Op. cit., Roesel, F. (2017), Blesse, S., and Roesel, F. (2019). See also, for example, Gendźwiłł, A., and Kjaer, U. (2020), “Mind the gap, please! Pinpointing the influence of municipal size on local electoral participation,” Local Government Studies, forthcoming.

[21] Cancela, J., and Geys, B. (2016), “Explaining voter turnout: A meta-analysis of national and subnational elections,” Electoral Studies, #42, pp 264-275; Van Houwelingen, P. (2017), “Political participation and municipal population size: A meta-study,” Local Government Studies, #43(3), pp 408-428; McDonnell, J. (2020), “Municipality size, political efficacy and political participation: A systematic review,” Local Government Studies, #46(3), pp 331-350.

[22] The correlation is highly statistically significant at the 1% level in both countries with t-values of the coefficient of 5.85 (eastern Germany) and 3.71 (Ukraine). The R² is 0.18 (eastern Germany) and 0.07 (Ukraine).

20 February 2026

Місцева статистика: Як перетворити розрізнені...

У Києві відбулася стратегічна зустріч "Статистика громад", організована Державною службою статистики України за...

20 February 2026

I_CAN launched a nationwide rollout of its Public Investment Management Training Programme for local governments and...

20 February 2026

Language of Development Part 2: Funds and Instruments of EU Cohesion Policy

Language of Development Part 2: Funds and...

With the “language of development”, we describe not only the goals and principles of EU regional policy, but also...

19 February 2026

Анонс: вебінар «Обговорення змін до Порядку...

Які практичні кроки мають здійснити керівники та педагоги, щоб ефективно впровадити ключові зміни до Порядку...